By Leyla Sayfutdinova

The Flame Towers of Baku were built in 2013 and soon became one of the city’s most recognized symbols (see fig. 1). A modern, glass-clad, high-rise complex composed of three towers resembling flames of a fire is home to an office plaza, a luxury hotel, many apartments, and shops. The Flame Towers have transformed the city’s skyline and quickly become iconic. Together with a few other contemporary buildings, such as Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre (2012, see fig. 2) designed by “starchitect” Zaha Hadid, Crystal Hall built for the 2012 Eurovision contest (see fig. 3), and SOCAR (State Oil Company of Azerbaijan Republic) Tower (2015, see fig. 4), the Flame Towers are often presented as part of the modern rebranding of Baku, thought to be modelled upon the urban architectural aesthetics of Dubai. The novelty of the new architectural icon is emphasized by both those who support Baku’s recent urban transformation as well as the critics who decry the buildings for their departure from traditional architectural forms that utilize local materials, particularly sandstone, and traditional skills, such as stone masonry. Since their construction, debates on whether the Flame Towers are ‘beautiful’ or ‘ugly’, whether they deserve to be a symbol of Baku or not, whether they are intended for ‘tourists’ or the ‘locals’ have been ongoing. What is more, the high-rise towers dwarfed Baku’s old symbol, the Maiden Tower (see fig.5), and replaced it in tourist and promotional materials. Located in the symbolic ‘heart’ of Baku, the walled Inner City, the 30-meter-tall medieval sandstone structure has long been a repository of urban memory and imaginaries.

Zoroastrian legacy

The shape of the Flame Towers alludes to the ancient history of fire worship in the region and to the popular etymology of the name “Azerbaijan”, commonly translated as “the land of fire.” The shape thus reflects the current “nation-branding” practice, which draws on ancient history in creating a new, yet recognizable identity for the country. But if fire symbolism has such deep roots in Azerbaijan, what then is so new about this building? Why is it so contested? Is it the novelty of the building’s aesthetics, its materials, or something else? In this blog post, I explore some of the meanings assigned to the Flame Towers to understand their place in Baku’s symbolic cityscape.

Although the popular etymology of “the land of fire” is disputed (another theory derives the name “Azerbaijan” from the toponym “Atropatene”, which refers to an ancient Persian province south of the Araxes River. The province was named after Atropates who ruled it in the 4th century BC), the Absheron peninsula where Baku is located has indeed been known for its self-igniting fires for centuries. Arguably, the eruption of such fires from the sub-surface reserves of oil and gas was one of the reasons why the region played an important role in the development of Zoroastrianism. For Zoroastrians, fire is worshipped and considered sacred as it represents the divine light and hence the origin of life. Zoroastrianism dominated the area from the 1st to 7th century AD. Following the Arab conquest in the 7th century and the subsequent spread of Islam, most Zoroastrians either converted or fled to India, where they became known as Parsis. As the numbers of Zoroastrians dwindled, most of their sites of worship were abandoned or destroyed. Yet, in the village of Surakhany, near Baku, one such site, known as Ateshgah (see fig. 6), was renovated at the end of the 17th century, most likely by pilgrims from India. Like many of the older Zoroastrian temples in the area, it was built around a self-igniting fire. By the end of the 19th century, Ateshgah lost its religious importance, as the extraction and refining of oil in the area were seen to contaminate the purity of the sacred fire and eventually exhaust the subsurface reserves of natural gas, which fed it. Ateshgah has since been converted to a touristic site and in 1969 connected to the city’s gas network.

Nowadays, only one self-igniting fire remains in the vicinity of Baku, known as Yanar Dag, or “burning mountain” (see fig. 7). Still, eruptions of fire from under the ground occur from time to time, mostly accompanying eruptions of mud volcanos, both on the Absheron Peninsula (Lokbatan) and in the Caspian Sea, such as this recent spectacular eruption on an uninhabited island 50 km south of Baku. While there are no practicing Zoroastrians in Azerbaijan today, in popular discourses these natural fires and the hydrocarbon reserves from which they flare up remain connected to Zoroastrianism. This link to fire worship could be observed in the social media discussions of the recent eruption.

Oil boom legacy

Despite this long history of fire worship, the symbolism of fire was not common in Baku until the 19th century. The medieval coat of arms of the city, for example, which can be seen to this day on the walls of the Inner City citadel (see fig. 8), has nothing to do with fire. It depicts a head of a bull between two lions – a reference to Persian symbolism of power and possibly the victory of Shia Islam over Zoroastrianism.

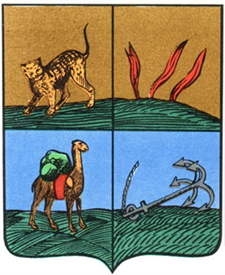

It was the Russian administration in 1843 that first introduced the symbol of fire to Baku’s heraldry. By this time, Russian military engineers were already working in Baku’s oil fields and experimenting with the drilling and refining of oil. In the early version of the city’s coat of arms (see fig. 9), the fire was not yet very dominant. It was one among several symbols, which also included a lion, the old symbol of power, a camel as a symbol of trade, and an anchor as a symbol of a seaport.

The wide adoption of fire symbolism took place at the time of the oil boom, which began in Baku in the 1870s. The invention of kerosene in 1854 started the accelerated development of oil extraction across the world. Baku was one of these pioneering sites of the emerging oil industry, producing at the turn of the century half of the world’s oil. Industrial installations transformed the former sacred landscape of Zoroastrians: for example, Surakhany, the village with the fire temple, became a site of an oil field and a refinery connected to the city with a pipeline. At the same time, the industry memorialized Zoroastrianism. Thus, the Nobel Brothers Company, the largest oil producing company in Baku at the time, drew on Zoroastrian symbolism in their corporate branding: they put Ateshgah on their company logo (see fig. 10) and named their first oil tanker “Zoroaster” (see fig. 11).

In 1877, around the same time as the Nobel brothers took Zoroastrian symbols for their company, the city administration adopted a new coat of arms. The new version had three flames in the centre of a heraldic shield, topped with a crown (see fig. 12).

An architectural depiction of this symbol can still be found on the citadel wall where it was installed in 1906, near the building of the Baku City Duma (Council) (see fig. 13). Since then, the three flames became a recurring symbol of Baku, reproduced on all subsequent coats of arms and city emblems. Thus, the Soviet coat of arms, reinstated after several decades in 1967, retained the three flames along with the black background from the Tsarist times (see fig. 14). The current version with the blue background was adopted in 2001. It retains the three flames and the sea waves with a new addition of a black line under the green/gold sea waves that depicts oil (see fig. 15).

Although the heraldic flames were used on Baku insignia in the Soviet period, it was during the post-Soviet independence that they came to dominate the city and state emblems. Thus, the national coat of arms, adopted in 1993, also features a flame (see fig. 16). On the streets of Baku, the symbol of three flames can be found everywhere, from building walls to streetlights and even rubbish bins. The logos of two international mega-events held in Baku in the 21st century also feature flames, such as the logo of the Eurovision contest (2012) and the 1st European Games (2015).

Burning for the Nation

Fire symbolism in Baku is thus not new but it is neither as ancient as the references to Zoroastrian history suggest. It dates back to the oil boom in the 19th century. For Baku specifically and Azerbaijan more generally, that oil boom fuelled industrialization, modernization as well as the development of the country’s national identity. The symbolic link with the nation was further strengthened during the Soviet period, with the tradition of eternal fires commemorating fallen heroes. The tradition was adopted in the Soviet Union after WWII and was widely used to commemorate soldiers killed in the war. It is not by chance, therefore, that the Flame Towers are located just outside the Alley of Martyrs, a cemetery where the victims of the Soviet invasion in 1990 and the soldiers fallen in the Karabakh war are buried. And although a more traditional stone-clad eternal flame (see fig. 17) frames the other end of the Alley, the Flame Towers amplify its symbolism. At night, the LED screens on the tower light up in the colours of the national flag – and thus the skyscraper brings together the symbolism of both oil and nation (see fig. 18 and 19). Importantly, the national flag itself was first raised in 1918 – the last year of the pre-Soviet oil boom.

The iconic Flame towers, therefore, draw on symbols and memorialisation traditions that have been well-established throughout the last 150 years. But if the symbolism of the Flame Towers is so well-established, why are they so controversial? Beyond the novelty of the glass-clad architectural style, I suggest that another departure from well-established memorialization practices is at play here. The medieval Ateshgah and Maiden Tower are both museums and public buildings, open and accessible to anyone. The recently built Heydar Aliyev’s Cultural Centre and the Crystal Hall concert venue are also public buildings, although they are more exclusionary and tailored to a more elite audience. Unlike any of these buildings, however, the Flame Towers are privately owned and constitute a luxury commercial property with office space, hotel rooms, high-end boutiques, restaurants, and apartments. It is thus the most exclusionary of the new iconic buildings. In this, the high-rise complex symbolizes not only the rootedness of oil modernity in Azerbaijan’s history, but also a particular moment in the present and perhaps a direction for the future. The luxury business centre in the shape of the fire flames becomes literally a shining symbol of Azerbaijan’s 21st century oil capitalism, with all the wealth, glamour, social exclusion, and division that it brings.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 897155