By Sean Field

The UK’s consumer energy regulator, the Office of Gas and Electricity Markets (Ofgem), announced on 6 August 2021 that it will increase the rates that energy companies can charge consumers for energy beginning 1 October. This increase comes on the heels of a rate increase that came into effect only half a year earlier, on 1 April, that pushed up household gas bills by an average of £90/year. It is estimated that the new increase will raise the cost for households by another £140-155/year for natural gas.

Ofgem explained the energy rate increase is necessary because of surging global natural gas prices that have driven the wholesale cost of electricity and gas up. In the UK, natural gas is widely used for heating, cooking, and for the industrial generation of electricity. 87% of UK households use natural gas to heat their homes and it has increasingly displaced coal for electricity generation. The price increase, Ofgem said, reflected the “legitimate costs of supplying energy” that suppliers were entitled to pass on to consumers.

The announcement raised alarms about the increasing cost of energy and growing energy poverty. In Scotland, where the average pre-tax income for employees is £25,600, it is estimated that about a quarter of all households are ‘fuel poor’ – meaning they spend more than 10% of their net income after other household expenses on heating and the funds leftover are insufficient to support a reasonable standard of living. Single-parent households are the most financially vulnerable to rising energy prices, a situation made worse by un/under-employment caused by the COVID 19 pandemic. Acknowledging this reality, Chief Executive of Ofgem, Jonathan Brearley, recently said:

This recent rate increase raises several questions, including: How does the UK natural gas system work? And how are natural gas prices in the UK determined?

In this blog post series, I examine the UK’s natural gas infrastructure, the market dynamics behind rising global natural gas prices, and who will be affected the most by Ofgem’s rate increase. In doing so, I advance the discussion put forth in Miles Oglethorpe’s and Ewan Gibbs’ recent blog posts on the UK’s industrial energy histories and the entanglement of these histories with the present. In this part one, I show how the deregulation and financialization of UK natural gas over the last couple of decades has exposed UK consumers to the geopolitics of natural gas pipelines and fluctuations in financial market prices for natural gas. I address natural gas taxes, environmental levies, and domestic energy suppliers in part two of this series.

How does it work? Natural gas infrastructures in the UK

Natural gas infrastructure in the UK has existed for well over a century. Gas works originated as a byproduct of the coal industry and local networks of natural gas pipelines delivered fuel to illuminate streetlights and the corridors of tenement buildings in cities across the UK.

Today, the UK sources 44% of its natural gas from reserves in the North Sea and the East Irish Sea. 47% of the UK’s natural gas is imported via pipeline from Norway and Russia (relatedly see our two posts on Brent crude oil infrastructure: part 1 and part 2). The remaining natural gas arrives as Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) imported via specialist ocean tankers that store it in liquid form at -160 °C. While natural gas supply networks in the UK have long been regional and pipeline-bound, the development of seaborn LNG tankers and infrastructure over the last couple of decades have made it into a truly globalized hydrocarbon commodity.

The companies that bring gas into the UK market (from offshore or elsewhere) are known as ‘gas shippers’. They sell gas on the wholesale market to ‘gas suppliers’ that sell to consumers. From the point where it is shipped in the UK, to the point where it enters localized distribution networks, natural gas travels through an intricate network of high-pressure pipelines, storage facilities and transfer points called the National Transmission System.

Benchmark spot market prices for UK natural gas are set at the National Balancing Point (NBP). The NBP was introduced by British Gas in 1996 (via the 1996 Uniform Network Code) as a central point for wholesale spot market prices to be set. Located at an unknown location in the UK, the NBP is part of the National Transmission System and is a key juncture where British Gas’s high pressure natural gas pipelines intersect. This hazy virtual intersection is the place chosen to signify where shippers transfer gas to suppliers (see Fig. 1).

Prior to establishing the NBP, spot markets for natural gas in the UK had developed at the Bacton (England) and St Fergus (Scotland) gas terminals over the previous decade. Natural gas spot markets were relatively new then and followed from the privatization of state-owned British Gas by the Thatcher government in 1986 (see Fig. 2). The establishment of the NBP signified a new form of planned privatization. The first of its kind in Europe, it allowed natural gas prices to ebb and flow with the free market, but the government provided the framework in which it operated by specifying a centralized location for spot prices to be benchmarked. It also helped set the stage for the establishment of natural gas futures markets in the UK.

Only a year after the NBP was created, in January 1997, London’s International Petroleum Exchange (IPE) began trading natural gas futures based on gas exchanged at the NBP under then Prime Minister John Major. Just days prior to futures trading beginning, IPE CEO Lynton Jones remarked: “IPE has been intimately involved in the deregulation of the UK gas industry” and that he hoped “the establishment of this futures market will help contribute further” to the free-marketisation of natural gas.

Jones was correct, the IPE futures market opened up a new era of financial trading on UK natural gas that flourished in the following decades. Moreover, this financial infrastructure linked futures prices for natural gas with UK spot prices for natural gas. The rates British consumers would pay for energy hereafter were not just the result of natural gas exchange on the physical market but on futures market as well. As we explain in our blog post on how futures markets and spot markets work together, futures prices influence spot prices and spot prices influence futures prices. This is because what financial buyers and sellers are willing to pay in each of these markets for natural gas is influenced by their current and future price expectations, and because spot and futures prices are connected by financial traders that can simultaneously trade future and spot contracts, as we have explained at greater length elsewhere.

International Petroleum Exchange (IPE) was bought in 2001 by ICE, a major corporation that specializes in providing electronic exchange house and financial data management services (see our blog post where we discuss ICE in relation to the trading of the Brent benchmark for crude oil). Today, the NBP is a virtual place where ICE UK Natural Gas Futures contracts are physically settled. When ICE UK Natural Gas Futures expire, they result in an obligation to physically exchange natural gas at the NBP. This is relatively rare though, because most buyers and sellers ‘reverse out’ of their contracts before they expire (see our blog post where we explain ‘reversing’). ICE UK Natural Gas Futures contracts are most commonly used by commercial buyers and sellers to hedge against changes in the price of natural gas, and by investors as an investment vehicle for energy. The NBP’s regional counterparts in the United States are the Henry Hub in Louisiana and in Europe the Title Transfer Facility (TTF) in the Netherlands. ICE UK Natural Gas Futures contracts and NBP spot prices are the benchmarks by which current and future natural gas prices in the UK are set. And, these now integrated financial and physical UK infrastructures, are part of a global transportation and pricing infrastructure for natural gas (see Fig. 3)

The exchange of UK natural gas between shippers and suppliers happens in a few ways. Much of it is bought and sold well in advance of physical delivery. Some shippers and suppliers enter into direct one-on-one contracts over months or years. More commonly, buyers and sellers will exchange natural gas on the Over-The-Counter (OTC) market. Using this form of trade, shippers and suppliers will agree to exchange natural gas at specific intervals over specific periods of time – within-day, day-ahead, monthly, quarterly, seasonally or annually. The wholesale prices at which shippers and suppliers exchange natural gas are influenced by future and spot prices, which account for about half of the cost that consumers pay for gas. The remaining costs that consumers pay can be attributed to the cost of delivery, the profit margins of suppliers, taxes and environmental levies – I take up these topics in the next part of this series.

Geopolitics and rising global natural gas prices

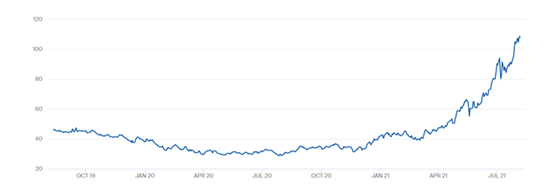

Ofgem’s recent decision to allow suppliers to charge consumers more for natural gas was officially attributed to rising wholesale UK natural gas prices. The price of the September 2021 ICE Future Contract for natural gas has more than doubled between January and August this year (see Fig. 4), and the price of other ICE UK natural gas futures contracts have risen as well. As a proxy for future prices, it means that suppliers are paying more for gas to be delivered in the months ahead than they previously had paid. It also means that buyers and sellers on the futures markets are expecting spot prices to be higher in the future months than they were previously.

Multiple reasons have been postulated for the recent rise in UK natural gas prices, such as global cuts in natural gas production, increased global gas consumption, and low levels of natural gas storage in Europe and around the world.

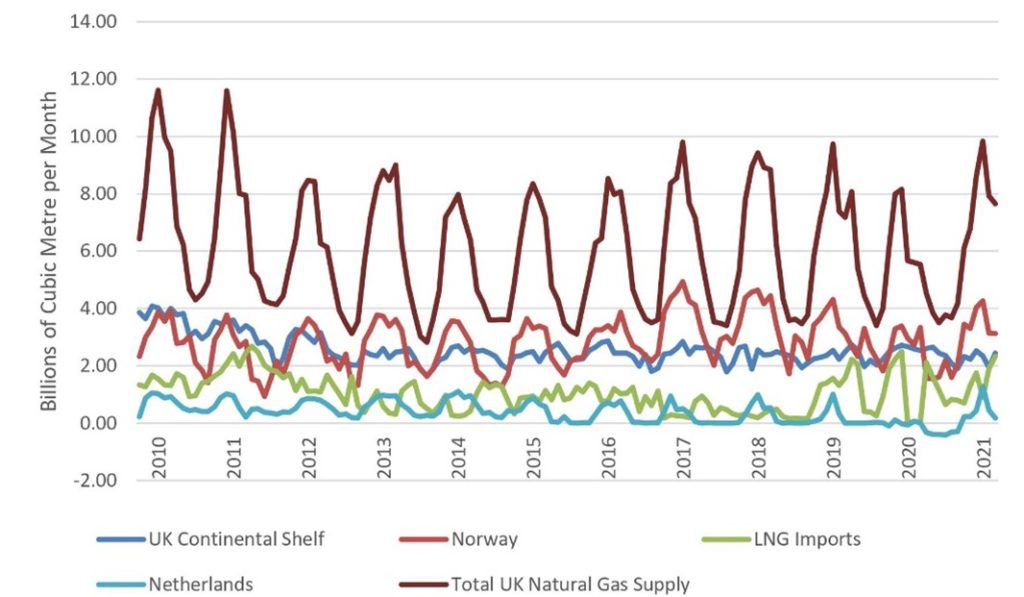

Consumption of natural gas globally, however, has remained relatively unchanged over the last few years – rising by 1.5% in 2019 and falling by 1.9% in 2020. According to the International Energy Agency, global demand for natural gas is expected to rise by 3.2% in 2021 – driven by extreme weather, economic recovery, and fuel switching from coal to natural gas. In the UK, the supply of natural gas and its sources have remained relatively stable for a decade, rising and falling with seasonal demand (see Fig. 5).

Production too has remained relatively stable. In the US, which accounts for a quarter of natural gas production globally, data indicate that production has been relatively unchanged over the last year and stores are well within expectations. While some countries reduced production, like Norway, others increased production, like China. Overall, natural gas production was relatively unaffected by COVID19 in 2020, falling by less than 3% globally. These data indicate that global production and consumption have remained relatively steady over the last couple of years, which suggests that the natural gas supply and demand alone does not account for the sharp rise in UK energy prices.

However, European supplies of natural gas are at historic lows – at roughly half of what they were in 2020. The reduction of natural gas being stored has reportedly been the result of a drop in gas shipments from Russia to continental Europe. Russia accounts for about a quarter of global natural gas production with vast proven unextracted reserves underground, and it supplies about 40% of the natural gas consumed in Europe each year. This reduction has sparked fears of a regional natural gas shortage across Europe this winter, which has pushed up natural gas futures prices as well as wholesale spot prices.

UK natural gas consumers in the crosshairs – geopolitics, deregulation and financialisation

Rising wholesale natural gas prices, that sparked Ofgem’s rate cap increase for UK consumers, thus appears to be the consequence of geopolitics and the integration of UK’s natural gas infrastructure with global gas and financial markets. From the privatization of British Gas to the establishment of UK natural gas futures contracts, what we see today is the legacy of the deregulation and financialization of UK energy.

The data above suggest that there is no shortage of natural gas in the UK or around the world. Unconventional extraction technologies in the US have made more natural gas available than ever before and existing conventional reserves across Europe are expected to last for many decades to come. The expectation of potential regional shortages spurred by a geopolitical tug of war between Russia and western European nations appear to be inflating future natural gas prices, which are inflating spot prices and the price suppliers pass on to consumers. What this indicates is that since natural gas futures markets were introduced in 1997, British consumers have been exposed to the ebb and flow of globally integrated ICE financial futures markets. It also indicates just how interconnected the UK’s physical natural gas infrastructure is with the rest of Europe’s, as well as its reliance on pipeline imports from European countries.

It is yet to be seen whether sea-borne shipments of LNG will supplement regional geopolitical pressures associated with natural gas pipeline politics. In 2020, the UK sourced most of its imported LNG from Qatar, followed by the United States and Russia. What is known, however, is that Russia will continue to be a natural gas supplier to Europe for the foreseeable future, and that Ofgem’s price cap increases will affect about 15 million households across the UK – roughly half the population – who are not on fixed rate contracts.

In the next part of this series, I take a closer look at which UK consumers will be affected most by Ofgem’s rate cap increase and examine the UK’s ‘big six’ consumer natural gas suppliers.