By Sean Field

On 6 October 2022, the company responsible for managing the UK’s electricity transmission and distribution infrastructure, National Grid, warned that the UK could face rolling blackouts over the coming months due to energy supply shortages. In its forecast, it cited the combination of high winter demand, low renewable energy generation, and insufficient natural gas supplies caused by the war in Ukraine.

Shortly after the announcement, the Executive Director, Fintan Slye, of the National Grid’s subsidiary that is responsible for balancing supply and demand, National Grid Electricity System Operator ‘ESO’, sought to ease concerns by suggesting that he is “cautiously confident” that no such blackouts will take place. The combination of “contingency” coal-powered electricity generation and National Grid’s “innovative Demand Flexibility Service”, he said, would “compliment the robust set of tools we already use to balance the electricity system every day”.

The UK Minister for Intergovernmental Relations and Minister for Equalities, Nadhim Zahawi, also sought to ease public concerns by arguing that rolling UK blackouts this winter are “extremely unlikely”. Yet, he considered it prudent to “plan for every scenario”. This easing was undermined when National Grid’s CEO, John Pettigrew, issued fresh warnings that the British public should indeed be prepared for rolling blackouts on “those deepest darkest evenings in January and February”.

In Part 1 of this series, published in September 2021, I outlined how rising UK energy bills were connected to the financialization of energy and the deregulation of British Gas, leaving households and businesses exposed to wholesale price volatility, including volatility caused by rising geopolitical tensions between Russia and Europe.

A lot has happened since then. Geopolitical tensions have escalated into war, Ofgem has raised the energy price cap for electricity and natural gas twice more since September 2021, and dozens of UK energy suppliers have declared insolvency. Households and small businesses in the UK have resultantly struggled to keep up with the energy price hikes and millions have been thrust into energy poverty. Now, people across the UK are also faced with the prospect of potential blackouts.

In Part 2 of this series, I explain how the UK’s energy crisis is a dual predicament of an energy price crisis and an energy supply crisis. I show how the UK’s electrical grid is balanced on the wholesale market for natural gas, which is pushing people into energy poverty as wholesale prices rise. Building on Part 1, I also show how natural gas dependency and insufficient UK natural gas storage capacities are threatening electricity blackouts this winter (as well as a crisis of heating). I conclude by arguing that it was possible to envision this crisis and to enact plans to avoid it. I also argue that better planning and oversight are needed to make sure this does not happen again.

UK Electricity Generation

Electricity generation in the UK began in 1878 with the operation of a hydro-electric generator at Cragside, Northumberland, England. Shortly thereafter in 1882, the world’s first coal-fired power station was established in London, kickstarting over a century of coal-dominated electricity generation across the UK and beyond.

With coal as the primary feedstock for electricity generation, power plants were established near industrial urban centres around the UK. Between the late-1880s and the mid-1920s, the UK’s coal-powered electricity system was a patchwork of private and municipally owned stations and transmissions systems that supplied homes and businesses on a region-by-region basis. It was not until the establishment of the Central Electricity Board (CEB) in 1926 that efforts were made to standardise transmission infrastructure and voltage. Taking responsibility for transmission and the security of the electricity supply on a national scale, the CEB set the stage for the national electricity grid to be established in 1935, when regional electricity networks in Manchester, Leeds, Newcastle, Birmingham, Bristol, London, and Glasgow were linked.

The UK’s electricity grid and generators were nationalised by the 1947 Electricity Act in conjunction with a wave of nationalisations across the UK in the post-WWII period. The grid was subsequently privatised 40 years later by the 1989 Electricity Act, under the Thatcher Government. In a memo supporting privatisation and touting the benefits of the “market” and “competition” to then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, dated 25 January 1988, Government Advisor John Wybrew argued that “electricity consumers, rather than the taxpayer, should bear the cost” of securing the UK’s energy supplies. This privatisation shifted responsibility for determining the future of the UK’s electricity system onto the private sector and the costs associated with it squarely onto consumers, paving the way for the electricity system’s current configuration of private-sector owned, but publicly regulated, patchwork of firms.

From Coal to Natural Gas

Coal dominated electricity generation well in to the twentieth century. In 1960, for example, 90% of electricity in the UK was generated by coal-fired power plants. But, over the next four decades, coal was increasingly replaced by nuclear and natural gas for electricity generation. As Ewan Gibbs documents in his book, Coal Country, the move toward non-coal sources of energy was integral to governmental modernisation plans in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the advent of North Sea oil and gas production in the 1970s.

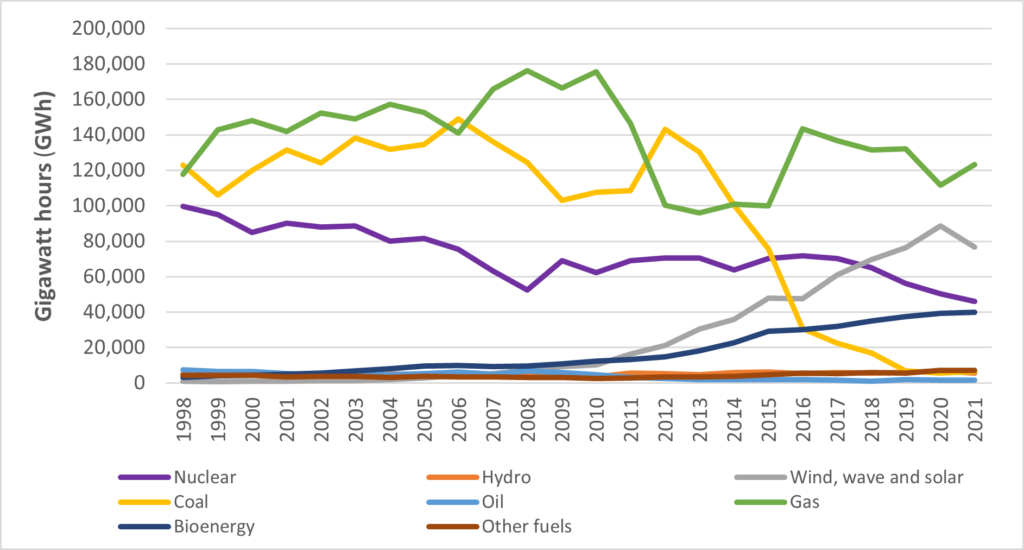

Over the last quarter century, natural gas has been the most important electricity generating fuel source in the UK (see Figure 4). In 2021, it accounted for 40% of electricity generation, followed by renewables (25%), nuclear (15%), and bioenergy (13%).

As I documented in Part 1, less than half of this gas is now sourced from the North Sea and, since the late-1990s, the wholesale price of this gas is determined by global commodity market trading rather than physical supply and demand alone.

Data Source: Digest of UK Energy Statistics (DUKES 5.1) produced by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS).

The Electricity Grid – Priced and Balanced on Natural Gas

The firm that manages the UK’s natural gas and electricity networks, National Grid, was founded in 1990 with the privatisation of the electricity system, and its shares are traded on the London Stock Exchange. It is one of the largest utility firms in the world, with subsidiaries in the UK and the United States, reporting an after-tax profit of £2.1 billion in 2022.

Regulated by Ofgem, National Grid is charged with ensuring there is enough electricity in the UK’s electrical grid at all times. This is a complex exercise in balancing supply and demand second-by-second. Undersupplies can result in blackouts and brownouts. Oversupplies can be temporarily stored via batteries but are otherwise wasted.

A Single Market Price for Electricity

While National Grid owns and operates electricity generating facilities in the United States, it is primarily responsible in the UK for moving electricity from where it is generated to where it is needed. Its basic function is connecting energy generators, who produce energy for sale at wholesale prices, with energy suppliers, who sell energy to households and businesses at retail prices. Wholesale electricity prices make up 50-60% of retail energy prices, with the remaining 40-50% attributable to network management expenses, operation costs, and profit margins.

In the early-2000s, UK electricity markets were reformed by the 2001 New Electricity Trading Arrangements (NETA) and the 2005 British Electricity Trading and Transmission Arrangements (BETTA). The aim of these reforms was to create a single wholesale market and price for UK electricity at a time when generation was dominated by natural gas and coal.

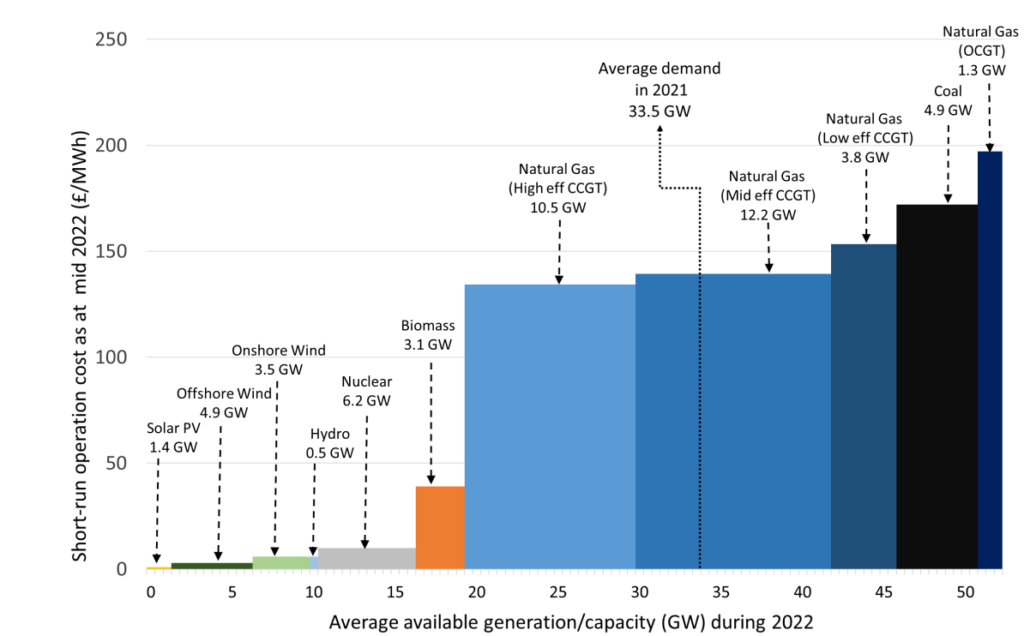

Managed and coordinated by National Grid, generators and suppliers buy and sell electricity in half-hour intervals, 24 hours per day, 365 days per year. Buying and selling between generators and sellers can be bilateral, meaning they can work it out between themselves, but they have to inform National Grid one hour before they physically trade electricity. Where there are no bilateral agreements or where supply and demand do not match, National Grid will manage buying and selling of electricity to make sure the balance is maintained. Electricity generators will submit price bids at which they are willing to supply electricity. National Grid will accept these bids up until demand is satisfied, beginning with the cheapest and ending with the most expensive. It will then set a single market price for electricity for “all market participants”, based on the last and most expensive electricity supply bid available to meet demand, every half hour.

Balanced on Natural Gas

Recent analysis has shown that meeting UK demand requires ‘mid-range’ efficient natural gas electricity producers to supply the grid over 80% of the time, on average (see Figure 6). The price of electricity produced from natural gas depends both on the efficiency of electricity-producing turbines and on the wholesale price of the natural gas that feeds them. Rises in the wholesale price of natural gas have driven up the wholesale price of UK electricity, which has driven up the retail electricity prices paid by households and businesses.

A “Bonkers” and “Outdated” Pricing System?

The founder and Chief Executive Officer of Octopus Energy, Greg Jackson, recently described the UK single market system as “bonkers” because wholesale electricity prices do not reflect the cost of producing energy for the most efficient producers. In August 2022, he called for this “outdated” system of pricing to be reformed. However, what would replace the current system of balancing supply, demand, and pricing is not clear.

Established at a time when the cost of natural gas was relatively low and stable, the current single-price system was designed to ensure sufficient supply “capacity at low cost”. This, of course, has been undermined by volatility in the wholesale price of natural gas and supply disruptions caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine. If wholesale natural gas prices had been relatively high or volatile when the single pricing system was designed, its formulation might have been different. The single price may not, for example, have been designed to hinge on the wholesale price of natural gas or the cost curve of ‘mid-range’ electricity producers. Meanwhile the current generating capacity and intermittency of wind and solar electricity facilities mean that solar and wind alone are unable to reliably supply the UK with the electricity it needs.

Moving away from a single market might mean pricing electricity differently by region (or “zone”), as is done in some countries (such as Italy, Sweden, and Norway), or according to how it is generated. This might mean, however, that households and businesses in some regions pay more based on their proximity to production facilities and how these facilities generate electricity. The other implication of a decentralised single-pricing system could be that electricity prices fluctuate up and down based on the availability of low-cost solar, wind, and natural gas electricity generation, further adding to energy price volatility and uncertainty.

From Bad to Worse – From Price Crisis to Supply Crisis

A related, but new, dimension of the UK’s energy crisis, is the potential energy supply crisis that threatens blackouts this winter.

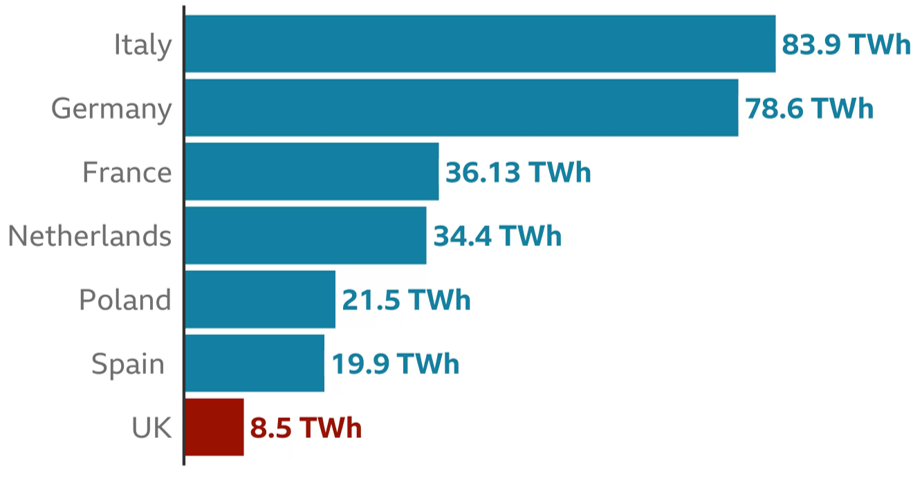

As the Centre for Energy Ethics noted in its evidence submission to the UK’s Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Committee in January 2022, the UK has relatively limited natural gas storage capacity compared to other European countries, as measured in terawatt-hours (see Figure 7). As of October 2022, the UK held 9.14 TWh of natural gas in storage, 94% of its current capacity limits. This is especially important because even though the UK is deeply reliant on natural gas for heating and electricity consumption, storage capacity is well below other European countries (see Part 1). France, by contrast, relies primarily on nuclear power sources to generate electricity, but still has far more natural gas storage capacity than the UK.

Source: Plummer R. 2022. Will Russia-Ukraine tensions push up UK gas bills? BBC.

The UK’s gas storage capacity was significantly curtailed in 2017 by the closure of the Rough facility, near Yorkshire, by Centrica – the parent company of British Gas and Scottish Gas. Prior to its announced closure, the Rough facility was reported to have accounted for 70% of the UK’s natural gas storage capacity.

With little natural gas storage available and insufficient renewable energy generating capacity, the UK is underprepared for natural gas supply disruptions from Europe caused by the war in Ukraine. It is dependent on a steady stream of natural gas imports to meet domestic demand (see Part 1).

The Centre recommended that the Government invest in reopening the facility to bolster the UK’s energy storage capacity and invest in upgrading its technological flexibility to handle natural gas in the short-term and renewable fuels, including green hydrogen, in the long-term. Reports suggest that the Government has acted on this advice, with a Government spokesperson saying:

“It is sensible that all possible options are considered to maintain security of gas supply, and that includes the future of gas storage if required. In the longer-term, we are also exploring options and locations to store clean energy, such as hydrogen.”

However, these infrastructural upgrades will take years to be fully developed, leaving the UK dependent on a steady stream of natural gas imports to meet its energy demands in the short to medium term. Overall, this situation threatens to not only drive UK energy prices up further in the next few months, but also threatens blackouts this winter as the UK will not have enough natural gas supplies to keep up with electricity demands across the country.

Preparing for Blackouts and Planning for the Future

There are no easy short-term solutions to the energy price and energy supply crises facing the UK. While Russia’s war in Ukraine may have sparked the crisis, it was possible to envision an acute rise in natural gas prices and import shortages, and to put plans in place to mitigate such a scenario. While Russia’s military aggression has in recent months been blamed for this domestic turmoil, this energy crisis is the consequence of over thirty years of policy and infrastructural decisions by successive UK governments and corporations charged with managing our energy system.

In a blow to national commitments to curb climate change, the National Grid’s contingency plans for this winter state that coal might again play a significant role in helping the UK meet its near-term energy demand. Its “innovative Demand Flexibility Service”, meanwhile, is a scheme that seeks to “incentivise” electricity demand reductions at peak times, stoking memories of the early-1970s when households and businesses were forced to operate in candlelight as national electricity supplies ran low.

As we move into the winter months, the Centre for Energy Ethics has called for the Government to put safeguards in place to protect those unable to cope with the steep rise in energy prices. The Centre has also recommended that the Government plan for such “extreme” scenarios in the future by investing (and encouraging investment) in renewable energy generation and flexible energy storage infrastructures.

The present crisis will hopefully spark future plans that do not solely rely on ‘efficient’ markets or reliance on a single source of energy to meet the majority of the country’s energy needs. Future plans will also hopefully account for the potentiality of geopolitical turmoil and prompt critical reflections on how thirty years of successive privatisation have contributed to the UK’s lack of energy resiliency that will adversely affect the most vulnerable. However, only time will tell how our energy futures will unfold.