Why a change in mindset is necessary to protect the environment

By Andy Eskenazi

Right after finishing my master’s studies back in December of 2022, I moved to Austin, Texas, to start work as a manufacturing engineer in the semiconductors industry. With my bags packed, leased signed, and cowboy hat resting on my head, I embarked myself on an adventure to the lone star state with everything sorted out but one thing: commuting to work.

Long story short, I don’t drive. And while I do have a driver’s license, I choose not to use it, because driving is unnecessary when I can bike or take public transit instead. Having previously lived in Buenos Aires (Argentina), Hangzhou (China), and Philadelphia, I had never faced a major mobility hurdle due to these cities’ robust public transportation systems and extensive bike lane networks. However, Austin, like much of the United States outside of the northeast, was built mostly with cars in mind, and while efforts to expand and improve the city’s bus system and bike lanes are currently under development, the Texan capital still has a long way to go.

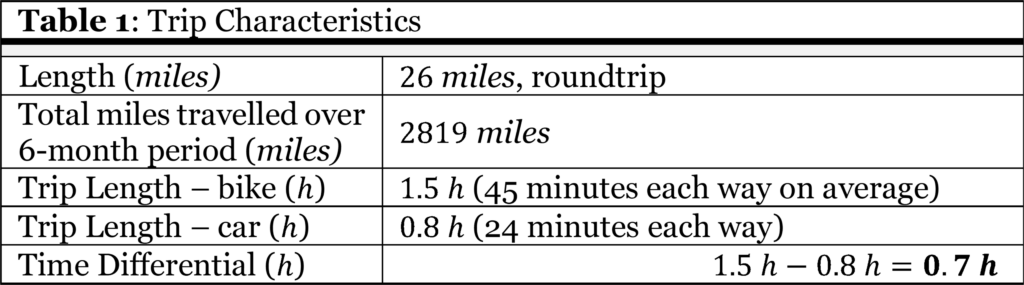

The challenge behind “How would I get to work?” tormented me every day prior to my arrival in Austin, until a bold idea emerged: biking to work! Although originally intended as a solution, biking soon became something greater than just a means of transportation from home to work and back, but a significant part of my life. Indeed, during my 6.5 month stay in Texas between January and August, I religiously biked to work 26 miles (roundtrip) every day, rain or shine, for a grand total of 2,819 miles. And to help with Austin’s extraneous heat (and arrive at the office relatively on-time), I did so on an eBike! Figure 1 below contains two pictures from my daily commute, while Table 1 summarizes the trip details.

Looking back at the past few months, I must confess that biking to work was no easy task. More often than I would have wanted to, the only possible path would have me riding on roads lacking bikes lanes and even sidewalks, next to massive trucks speeding at over 60 mph. Even on those roads where there were bike lanes, these would often be full of debris, quite commonly with nails that would cause my tires to pop, as Figure 2 (below) shows.

But despite these challenges, I greatly enjoyed my bike commute, not only because it would make me feel physically healthier, but also because it would consistently bring me to a happy mood, making my everyday engineering work more enjoyable! These effects, however, are not unique to my story, since multiple studies conducted in the past (across various geographies and demographics) have found that indeed, the choice of commuting transportation mode affects physical and mental health. Specific to biking, research has revealed that it is a less stressful experience than driving, it increases employee productivity, it improves commuters’ psychological wellbeing and mindfulness, and not surprisingly, it allows people to spend more time outdoors, which has been shown to enhance one’s quality of life overall.

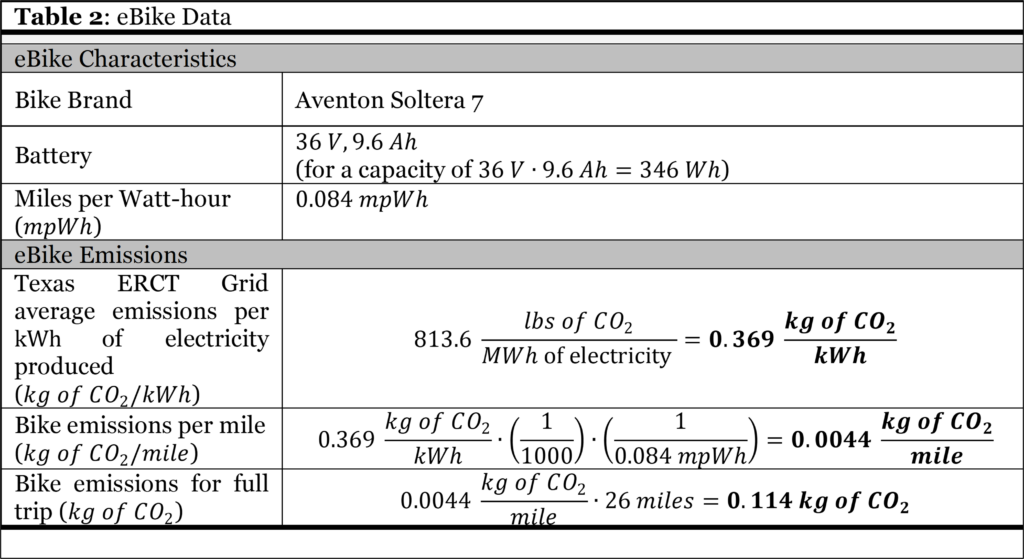

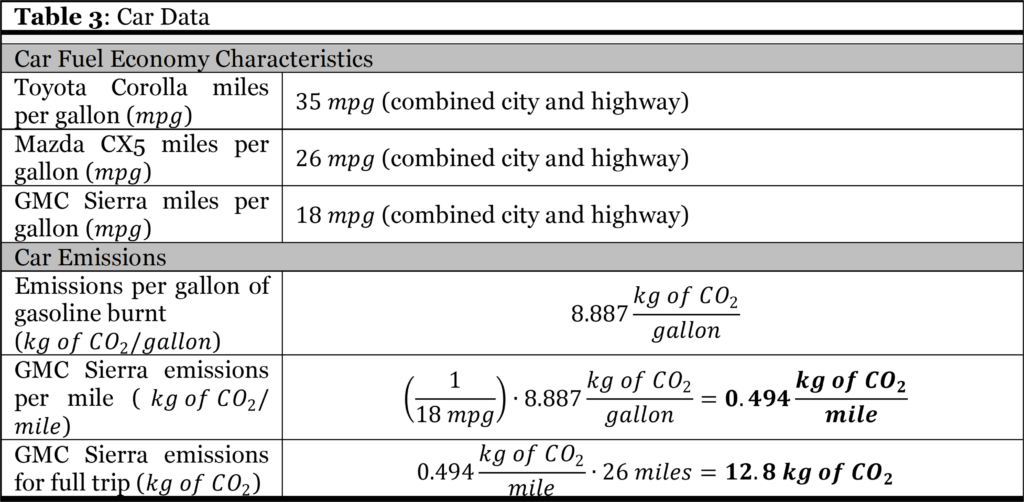

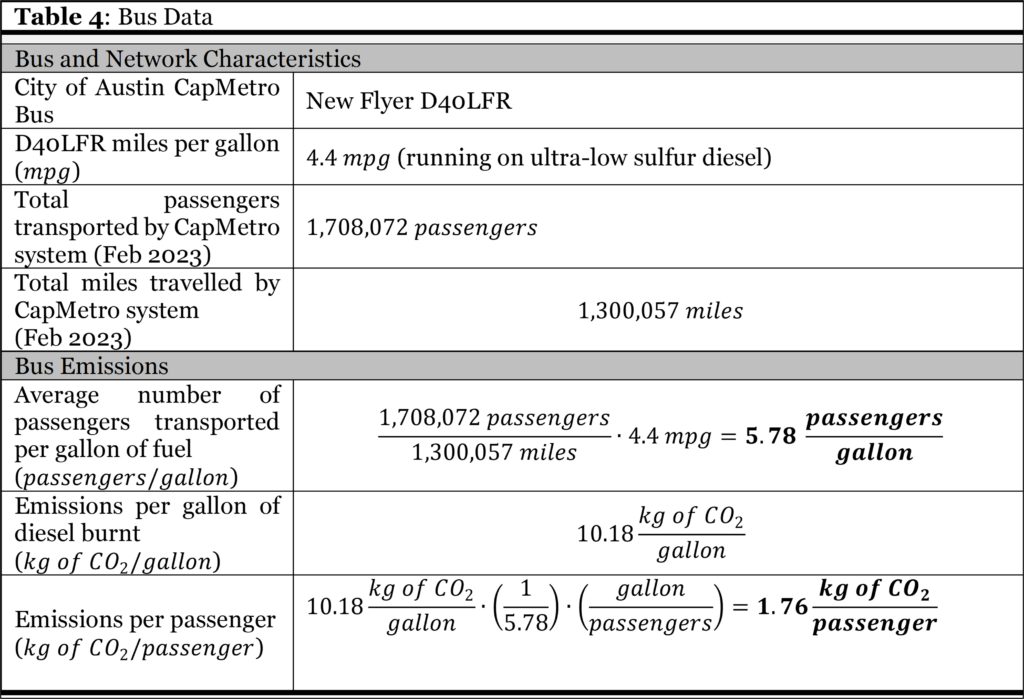

Although the roundtrip commute required an additional 42 minutes (see Table 1) compared to the driving alternative, I particularly came to appreciate this extra time to just think. Because it was in one of my rides, while looking at a GMC Sierra’s exhaust that I thought to myself, “what if more people rode their bikes to work? How much better would that be for the environment? How does my footprint on my bike compare to the Sierra’s?”. Excited to undertake this puzzle, I started writing the math, as is outlined in Table 2 through Table 4 below, seeking to compare the CO2 emissions produced by my eBike (at least due to the generation of electricity), against those of the GMC Sierra and the Austin CapMetro bus network.

Note: the 26 miles of my ride to work consumed about 90% of the battery’s capacity (with the highest pedal assist setting). As a result, the full 46Wh would correspond to 29 miles of range. The ratio between the two is precisely the reported mpWh value.

Note: the calculations for the CapMetro’s environmental footprint took a more systems-level approach than that for the eBike and cars. As such, the reported number corresponds to the average emissions per passenger on any trip, regardless of length, in the CapMetro bus network.

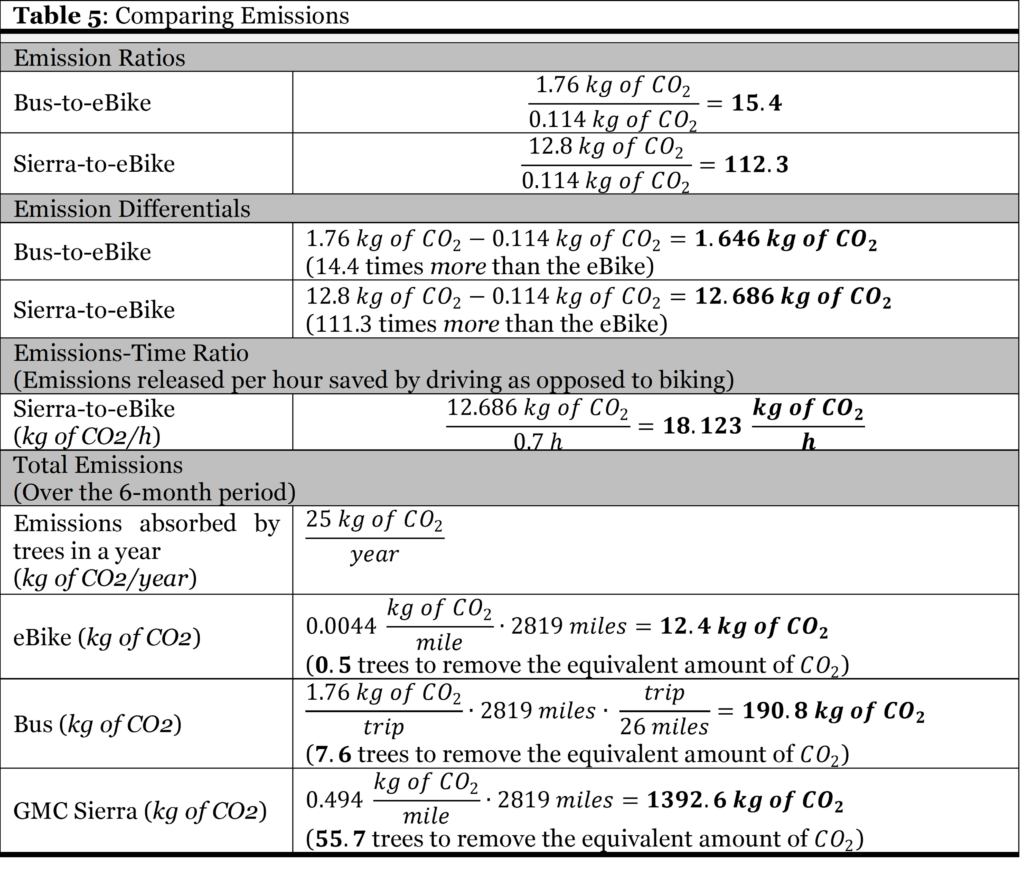

Overall, these calculations revealed that during my daily 26-mile roundtrip commute, in using the eBike, I was responsible for the release of a mere 0.114 kg of CO2 into the environment. This is a tiny fraction of the 1.76 and 12.8 kg of CO2 the bus and the GMC Sierra would have, respectively, released. As a point of comparison, repeating the same procedure outlined in Table 3 for two other popular models of cars in Texas, the Toyota Corolla and the Mazda CX5, returned roundtrip CO2 emissions of 6.6 and 8.9 kg respectively, performing right in between the bus and the Sierra.

As Table 5 highlights, these emissions corresponded to factors of 15.4 (bus) and an incredible 112.3 (GMC Sierra) of what the eBike theoretically produced (the Corolla and CX5 each resulted in factors of 57.7 and 77.7, respectively). In other words, it would take 112.3 roundtrips on the eBike to add up to the emissions produced by just one round-trip in the Sierra. Practically speaking, what this means is that driving a single week (5 workdays) on the Sierra would induce the same environmental impact as biking for more than a year and a half on the eBike! This extreme disparity in timescales illustrates clearly the magnitude of the environmental benefits of commuting to work on the eBike when compared to driving.

What is most interesting to me, though, is that if the argument for driving as opposed to biking narrowed down to time savings, Table 5 also demonstrates that an hour saved by driving on the Sierra would have released 18.123 kg of CO2. This amount is almost 1.5 times greater than what the eBike generated over the 2819 miles!

The goal of this blog post is not just to share my story and prove that indeed it is possible to survive in Texas without a car, as long as one is willing to endure the extreme heat and flat tires. More fundamentally, it is to illustrate a pixel from the ever-evolving, complex picture that climate change represents, even on the transportation realm alone. Although my experience serves as justification as for why Austin (and much of the country) could benefit from an expanded public transportation network as well as more and cleaner bike lanes, my hope is to instead reflect; not necessarily on ways of getting more people to bike to work, but really on the environmental impact of our actions.

Biking to work, at first, was a solution to my commuting problem. Soon, I discovered that it really represented some of the time and energy I was willing and able to invest to reduce my individual carbon footprint. However, asking all commuters to bike to work in the name of the environment would be unrealistic; there exists an extensive list of reasons why not everyone may be able to bike to work: lack of infrastructure, time constraints, long distances, employment conditions, physical mobility, or perhaps most importantly, not being able to access a bicycle in the first place. Even in my story, I took it to the extreme by enduring long distances across roads lacking biking lanes, all under the Texas sun.

Beyond biking to work as a case study, I want to call for a general change in mindset, urging everyone, not just commuters, to act consciously about the impact that our actions incur on the environment. Although my story demonstrates that biking to work minimizes our carbon footprint, it is not the only means to achieve the same goal. Thus, my hope is that everyone, not just commuters, not just those people that are not willing or not able to bike to work, can investigate other facets of their lives, and reflect on how we can act more sustainably. This call for a change in mindset extends to the public and private sectors as well, who play a crucial role initiating, promoting and maintaining environmentally friendly practices. For instance, governments can introduce and champion policy that extends a city’s bike lane network, and companies can deliver products, such as eBikes, that have reduced life-cycle emissions. This process is effectively a positive feedback loop; more bike lanes or eBikes could incentivise more people to bike to work, and in turn more people in the streets riding their bikes could precisely drive the expansion of a city’s bike lane network and the production of more efficient eBikes, overall reducing the number of cars being driven.

As a result, if there is one thing I learned biking to work in Texas, it is that only through a global change of mindset, across all levels of society, that we will be able to save our earth from its own collapse. Whether it is replacing some portion of beef in favor of plant-based foods in our diets, deciding to take the train instead of flying whenever not time-constrained, or extending the lives of single-use plastic products as opposed to disposing and buying more, an individual change of mindset, no matter how small, can have a long-lasting, positive impact. If accompanied by sound government policies and companies committed to delivering green products, these individual changes of mindsets and their associated impacts will multiply, become global, and truly reach all levels and facets of society.

However, to maximize our shots of reverting our planet’s catastrophic heading, it is imperative that these changes in mindset start right now.