Reflections following the first two parts of Looking North – a series of conversations between the worlds of art, literature, natural science and ecological conservation.

By Anne Daffertshofer

When we speak of energy, context determines meaning. I have learned that over the course of the past year. Together with my friends and colleagues Tori Champion and Emma Dodds, I started working on Looking North back in Spring 2022 – a project whose first two instalments would bring together a selection of four artists and four nature writers from Scotland to reflect on the concepts of landscape, nature, Northernness and energy.

Looking North invited artists whose work engages critically with these concepts, encouraging reflection on the framings, expectations, and realities of the Scottish landscape and our relationship to it. This blog post focuses on the works by Alex Boyd and Mhairi Killin. While Boyd’s Tir an Airm challenges the romantic image of the Hebrides in his photographic series of the MoD’s estate, Killin’s On Sonorous Seas explores the impact of anthropogenic sound pollution on whales. In each of the artist’s work, we encountered different imaginings of energy which ultimately opened new perspectives within those artworks. The works of Boyd and Killin address energy predominantly as relating to the Anthropocene, and specifically the devastating and lasting impact of human activity on the natural world – in their cases through bombardment and noise pollution.

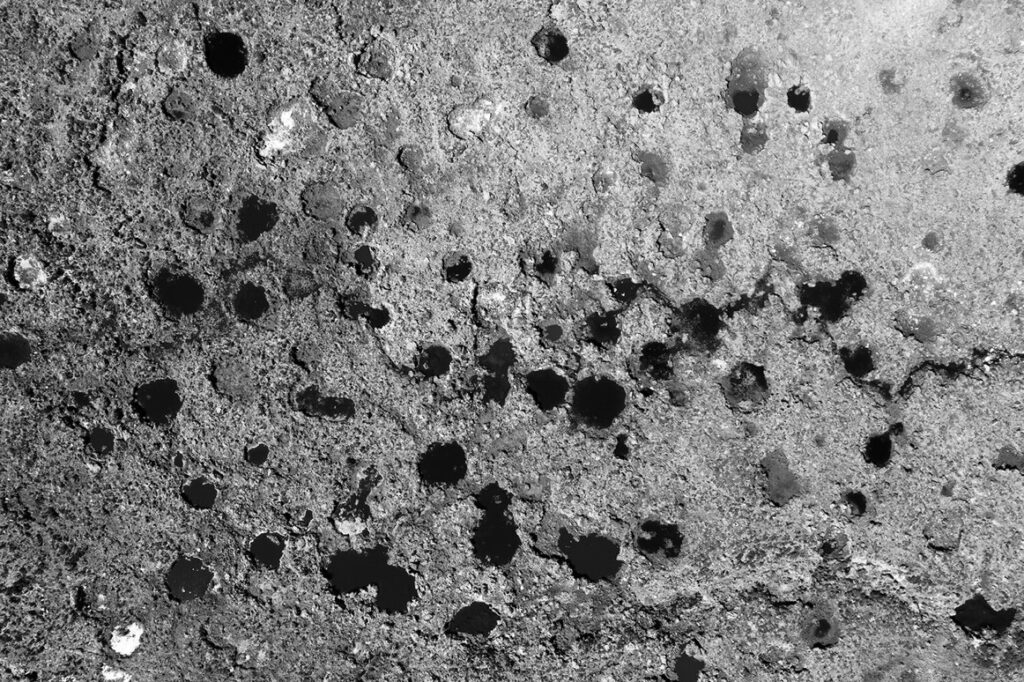

Captured in black and white, Boyd’s photographic series Tir an Airm presents perspectives onto a landscape which not many people have traversed. They reveal the vastness of the Hebridean weapons range that is part of the Ministry of Defence’s estate – a location that brings to the forefront many questions, contradictions and dilemmas of our time.

The unique energy of the place seems heightened by the brutal contrasts of beauty and destruction, nowhere more obvious than in one of the innumerable craters which Boyd’s photography reveals. Using drone imagery, he is able to transcend physical and topographical restrictions which render much of the military estate inaccessible to those on foot. The craters are remnants of some of the most destructive uses of energy humankind has developed. Those energies significantly directed the course of the twentieth century, enabling unprecedented levels of violence which shaped landscapes and their inhabitants. This anthropogenic fingerprint links the perforated landscape in Tir an Airm with its cousins across the world. In Europe, one’s mind may wander to the trenches and craters in Normandy, or even the forever-altered area around Chernobyl. Despite their differences, they are all manifestations of energies humankind have harnessed since the Industrial Revolution, and whose complex and wide-reaching effects can exceed our existence, and perhaps even our imagination.

In addition to the visible imprint on the landscape, long-lasting ecological changes follow bombardment. While Tir an Airm unveils ghosts of previous conflicts, it also links to current ones. In wake of the Ukraine war, NATO has been using the Outer Hebrides for large-scale military exercises and training. In Ukraine heavy metals and chemicals pollute air, water, land and soil, and the lives of both humans and non-humans are impacted significantly, leading to the abandonment of sites, decreased air, water and soil quality, and resultingly lower biodiversity production. The Ukraine war and particularly the destruction of the Kakhova Dam in June 2023 tragically brought the environmental cost of war to the forefront of public consciousness (e.g. the articles published by the UNEP and Emergence Magazine).

In Boyd’s photography, one detects shapes that look like dark circles from afar. The violence that preceded them feels abstract; that moment at which each circle emerged, following an explosion that catapulted intricate ecosystems up in the air, as pre-existing structures burst and animals, plants, and soil were blown up. Traces of past centuries suddenly exposed to particles, oxygen, and pollution of this present moment, the so-called Anthropocene. The age of man. In these moments timelines collide, opening a window into deep, geologic time, encouraging a moment to reflect and reframe.

Over time, the stillness which follows that destructive burst of energy renders each crater into a site of ecological transformation. In his Looking North talk, Boyd mentions the MoD’s sustainability magazine Sanctuary that is dedicated to highlighting their conservation initiatives. It conveys a strong sense of the MoD’s interest in drawing connecting lines between their activities and the potential for ecological conservation. This is partially due to much of their estate being protected from conventional development, providing conditions for ecosystems and biodiversity to thrive (e.g. “Demolitions + Amphibians = Population Explosion”) . The link between the destruction and negative impacts of anthropocentric landscapes turning into biodiversity havens has some parallels in floating oceanic plastic debris. Research has shown that a wide variety organisms can be found on much of the plastic floating in the world’s oceans. Yet this does not legitimise continued pollution. We understand it as overwhelmingly more destructive to existing ecosystems than can be balanced out by the construction of these new habitats. And in that, one may find a hint of sarcasm to be inherent to the MoD’s statement; repeated bombardment and environmental destruction is a constant companion to creating more craters than can “turn into habitats”. Boyd brings this tension to light, not just by showing marks of the environmental destruction invoked by military drills, but also in those images which show abandoned military equipment within the Hebridean landscape. They are time capsules – reminders of armed conflicts, pointing to past, present and future alike. They symbolise the discrepancy between expectation and reality; things, or put differently, uses of energies we silently accept and allow to happen as long as they are out of sight.

That is why military tests of that kind are outsourced to places the majority considers remote. That same “remoteness”, however, attracts not just the military, but also tourists escaping the mainland and its unforgivingly busy pace. To appeal to visitors, the tourism industry likes to idealise “remote” places as “the perfect escape”. The notion of remoteness often ties in with being difficult to reach from the centre, and so the journey to that escapist destination and the effort required, for example by taking a plane, a ferry or driving by car, directly relates to discourses on energy in the context of transport.

Killin’s work, also located in the Hebrides, moves us to the small island of Iona, two ferries away from the mainland. Hebridean islands, and Iona in particular are known for their special, spiritual energy. It is apparent in the rugged sea, the energetic waves, the strong winds. Time can feel different on those islands. When walking through bogs or feeling the tough surface of rocky cliffs – the past has noticeably shaped the environment. To Mhairi Killin the island is home. A place shared between human and non-human alike, one to which she feels spiritually connected, where nature feels close and like a constant and active component of everyday life.

The relationship between islanders and whales is one example of those ancient links. When washed ashore, their carcasses would sustain island communities, and their oil was used for many purposes during industrialisation. In fact, whale oil was thought to produce the best light which contributed significantly to the whale hunting business, decimating their populations. While the idea of whale oil lamps may sound foreign now, it tells of rapidly changing perceptions over a short period of time, accompanied by a cautionary tale on the effects of disregarding long-term environmental consequences of our decisions regarding energy. In the late nineteenth century, whale oil was gradually phased out and replaced with kerosene and petroleum, leading into an era of ever-increasing dependency on fossil fuels (on the relationship between whaling and fossil fuels, see this post on the Energy Blog).

In August 2018, a whale carcass was found at Traigh an t-Suidhe/ Strand of the Seat – at the North end of Iona. In the following weeks, another 117 beaked whale carcasses arrived around the Hebrides, Ireland, the Faroe Islands and Iceland. On Sonorous Seas explores that phenomenon, and particularly the impact of military sonar on deep diving whales.

Though sonar is an intense burst of energy, many people may not immediately think of its environmental impact. In part, this is because the frequency of sonar is too high pitched for human ears, and so situations in which we are confronted with it will be very limited. That may be in part why environmental issues to do with sonar, and more generally sound pollution, are not at the forefront of public discourse. On Sonorous Seas operates against that backdrop and raises the issue of “anthropogenic sound pollution” by exploring the mass whale stranding in that context.

It is a theme particularly relevant to discussions on the ethics of energy; anthropogenic sound (pollution) exists all around us. Within a maritime context, ship noise is one of the predominant sources, encompassing cruises, military purposes as well as fishing or cargo, of which 40% are for transporting fossil fuels (see this article published by Forbes and shared by the journalist Bill McKibben). Further factors include off-shore drilling, sonars, and seismic exploration naming just a few examples (for more information, see here). With help from an interdisciplinary team of collaborators, each of whom contribute their specialities and expertise, Killin points our attention to this often-ignored aspect of modern human activity.Using a variety of mediums, Killin exposes viewers to the world of underwater sound through a soundscape and video installation, that also comprises of drawings and sculptures. Drawing on the voices of science, art, music and poetry, Killin challenges the othering of underwater worlds and their portrayal as remote or empty. She does so by encouraging the audience to join her in a practice of deep listening. For that, she took inspiration from Pauline Oliveros who used that term to encourage intense attentiveness – an activity which, in times of the attention economy, is lacking in much of our everyday. On Sonorous Seas is the result of the many different kinds of deep listening which the artist undertook during the creation process, ranging from her research and conversations with collaborators, to listening deeply to underwater sounds using technological equipment. Working with the Hebridean Whale & Dolphin Trust, Killin joined their vessel on a ten-day voyage during one of NATO’s largest joint military exercises in Europe. She later described this experience as having ‘immersed her in a pelagic world of sound’.

Sound pollution is just one example of an unintended by-product of human activity. As Scotland aims to expand its current renewable energy production, investigating the ecological impact of offshore windfarms and tidal energy projects is vital. Collaborative projects such as the Marine Alliance for Science and Technology for Scotland project (MASTS), which develop modelling frameworks to measure and quantify the impact of these offshore developments are necessary to inform and guide policy. Their activities facilitate crucial knowledge exchange amongst specialists (see this paper).

Initiatives such as MASTS demonstrate the importance of collaboration and exchange, especially considering the scale and complexity of the issues humanity is currently facing. In some ways, this spirit mirrors the collaborative attitudes within the community on Iona. Mhairi told us that the island community has now taken energy matters into their own hands, establishing a community-owned energy company to generate sustainable energy for Iona which currently relies mostly on fossil fuels. There is a tension, Killin noted, between feeling close to nature and relying on environmentally destructive ways to generate energy, which is partly due to the island’s infrastructure (see Killin’s talk). The establishment of Iona Renewables provides an interesting case within the world of renewable energy, particularly in a market oversaturated with energy corporations that seem to know one goal only: maximising profits.

If you would like to learn more about Looking North, please visit our website lookingnorthtalks.com, watch the recordings and keep an eye out for the next blog post covering the works of Sophie Gerrard Drawn to the Land and Sekai Machache Profound Divine Sky. You can find Alex’s talk and his conversation with the author Cal Flyn on the CEE YouTube channel along with Mhairi’s talk and her event with the well-known activist and writer Alastair McIntosh.