By Riyoko Shibe

In 1924, the Grangemouth refinery opened under Scottish Oils Ltd., a subsidiary of British Petroleum. The company began operations by importing crude oil from the Persian Gulf through the thriving Grangemouth docks and following the energy transition towards petroleum products after the Second World War, the complex and the town expanded. Related industries like chemicals and plastics, which use crude oil and its derivatives as feedstock, also flourished. Currently, the refinery is one of six remaining in the UK, and the only one in Scotland. In 2005, it was sold to Ineos, a private multinational petrochemical company and in November 2023, the company announced the refinery’s closure and its plans to turn the site into a fuel import terminal. With refinery operations expected to cease in Spring 2025, the import terminal is set to employ only 100 people compared to current refinery employment which stands at around 500.

The closure announcement is another step in a long history of a town shaped and defined by government energy choices and corporate decision-making. Today in Grangemouth, we see continued investment into petroleum and huge profits for the sector, but with little returns for the workers and community who sustained the industry for over a century. The fact that there are fewer people working in these big industrial sectors obscures that we live in an industrial society, with petroleum in particular central to our modern economy, and whose products we all continue to rely on.

In a previous blog, Ewan Gibbs wrote on the centrality of energy to Scotland’s modern history. This post looks at Grangemouth as a localised example of this, using government archival documents, clippings from local newspapers, and oral history testimonies from Grangemouth residents who grew up under BP. Grangemouth’s story is one of how communities and workers are shaped by power relations formed through the operations of large states, major oil companies and global markets. With the refinery having been in operation for a century, and its scale of operations once vast and expansive, the town’s history forewarns the impacts of an unjust transition, and the pitfalls of centring private business and profits over communities and workers.

Grangemouth was first recognised under the Housing and Town Development (Scotland) Act in 1957. It was the first settlement to receive a grant under this act, facilitating the building of houses, a shopping centre and an industrial estate. Five years later, in 1963, Grangemouth was designated a ‘growth point’ under the White Paper for Central Scotland, with financial and fiscal inducements designed to attract new firms to the town and encourage development of existing firms. Incentives included grants towards new machinery and building construction, and investment into local public infrastructure like roads, water services and docks.

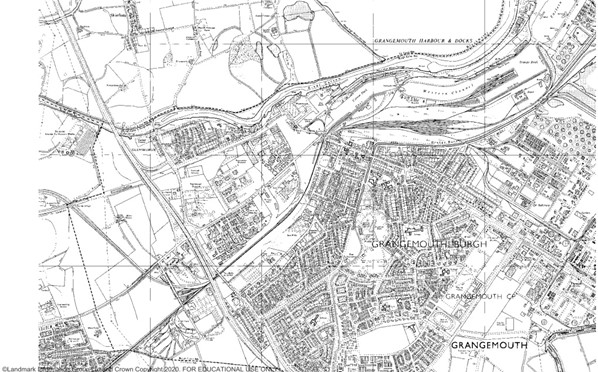

Official recognition of Grangemouth’s industrial potential went hand in hand with urban expansion. As well as secure jobs for workers, residents were housed through industrial development schemes of 1957 and 1963. 700 social houses were built under these proposals, overseen by a collaboration between Grangemouth Town Council, the Glasgow Corporation, and the Avon Housing Association (A.H.A.), which was formed by BP and BP Chemicals to house the company’s refinery and petrochemical workers. The town was celebrated in local and national press for its contribution to national economic prosperity, and as a result of the White Paper and Housing and Town Development act, Grangemouth’s population grew from 15,432 to 24,569 between 1951 and 1971. Figures 1 and 2 below show the extent to which the town expanded between these same decades, with Grangemouth in 1970, Figure 2, showing a much denser urban and industrial structure than in 1950, and a much larger town centre.

| Year | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 | 2021 |

| Population | 15,432 | 18,857 +3,425 (+22%) | 24,569 +5,712 (+30%) | 21,599 -2,970 (-12%) | 18,517 -3082 (-14%) | 17,906 -611 (-3%) | 17,373 -533 (-3%) | 16,240 -1133 (-7%) |

This industrial growth, however, peaked in the 1970s. The population figures in Table 1 serve as a rough proxy for this expansion’s limits, which reached a height of 24,569 in 1971, declining continuously through to the most recent census in 2021. What happened in 1971? Why did the decline begin there, and how is it related to the recent announcement of the refinery closure?

The answer can be found in early post-war expansion. Although this period seemed to promise a secure, stable, prosperous future for residents, it was in fact founded on a vulnerable economic base. The town’s industrial structure was the whim of government policy and private corporate power, and thus entirely dependent petroleum and its related products. Local government officials were aware of Grangemouth’s vulnerability and expressed this concern in meetings with the Scottish Office as early as 1962, only five years into the plan of industrial and urban expansion (SEP 17/73, Investigation of Sites for Industry). These concerns were articulated in terms of the capital and land-intensive infrastructure required by oil and petrochemicals, the relatively low number of jobs the industry generated, and BP’s monopoly over industrial land. Local officials argued that the town’s dependence on a single industry was constraining its capacity for industrial diversification and economic security.

The industry’s dominance over land was tolerated by the Scottish Office because of the wider contribution it would make to the national economy – “any industry is better than no industry” – and that the capital-intensity would be offset by its stimulation of related sectors and local economy during construction and operation (SEP 17/73, Scottish Economic Planning Board). For residents and workers, it was the material benefits provided by BP that offset the negative impacts. This was articulated in an oral history testimony provided by Anne Paterson, a Grangemouth resident born in 1940 who worked in BP Chemicals as a computer programmer during the early 1960s. Reflecting on how the industry was viewed locally, she remarked, “to begin with, wonderful. It was jobs, well-paid jobs. Secure work for life if you wanted it. They didn’t seem to mind things like pollution because Grangemouth was quite a smelly place in those days.”

The industry’s contribution to the national economy and BP’s provision of economic benefits for the town’s residents, though, merely rebalanced a scale rather than mitigated the extractive encroachment of BP’s dominance: issues of land dominance and capital intensiveness were never directly addressed and sat under the surface. It was in 1970 that the ramifications of the vulnerable industrial base came to the fore, leading to the continual population decline following its 1971 peak.

Under Edward Heath’s 1970-1974 Conservative government, a set of strategic decisions were made that broke down the relationship between Grangemouth, the government, and BP. First was the replacement of grant-based industrial incentives with a tax-based system in 1970 with Heath dismissing the grant scheme “indiscriminate and wasteful”, with particular reference to Scotland’s small size (PREM 15/636, Unemployment in Scotland). The removal of this system points to weakening moral economy powers that had justified issues in industrial expansion: “indiscriminate and wasteful” was a far cry from prior assessments of industrial support that had invested into Grangemouth for exactly the opposite rationale.

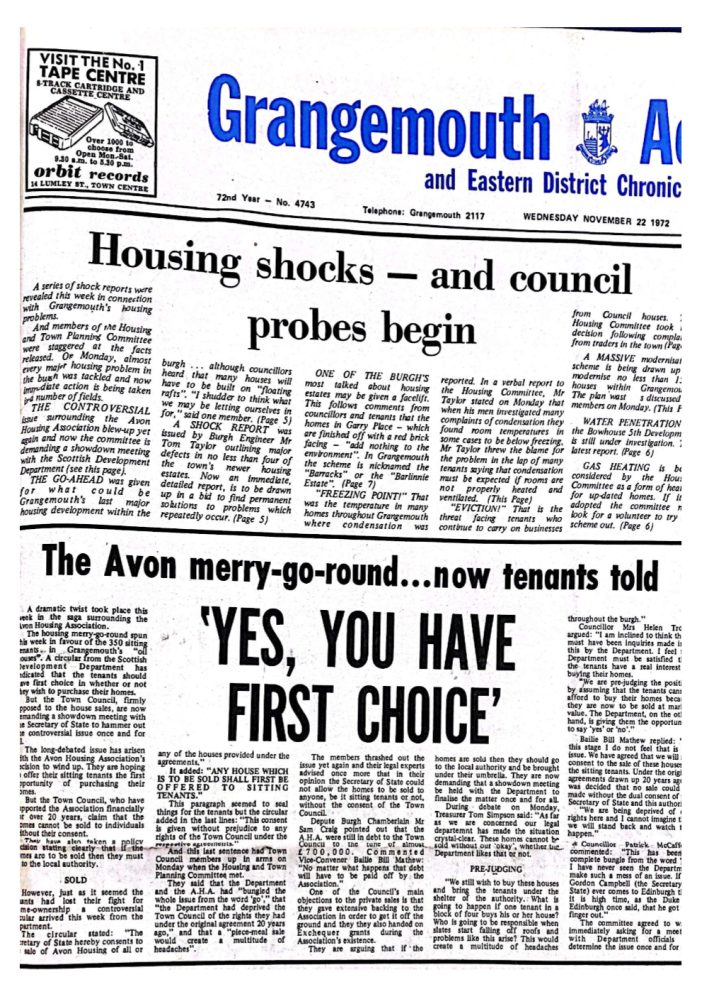

Second was the right-to-buy scheme in 1973 for 350 A.H.A homes; this marked the beginning of the end of social housing for oil and petrochemical refining workers in Grangemouth. With both BP and the Conservative government’s Secretary of State for Scotland vetoing the Town Council’s efforts to maintain ownership of the houses, the sale signalled the strengthening of liberalising pressures of the UK government. The newspaper clipping below is one of a series spanning eight months in 1972 of back-and-forth negotiations between the Grangemouth Town Council and A.H.A. about the sale of the houses. The clippings demonstrate the efforts the Town Council made to keep control of the housing, and how central the issue was to the town’s current affairs.

Finally, in 1975, Grangemouth Town Council was abolished and absorbed into the larger public authority of Falkirk District Council under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973. Prior to this, Grangemouth received non-domestic tax revenue of the refinery and associated industries and had control over how this was spent. Under the reorganisation of council boundaries, industry rates were distributed across the whole of Falkirk District Council rather than concentrated in Grangemouth, significantly diluting the benefits the town received from its industrial activity.

Without these material benefits, BP’s encroachment on land, the dominance of petroleum, and the lack of benefits associated with the refinery became increasingly intolerable for the Grangemouth community. This experience was compounded throughout the 1970s and 1980s as BP underwent intensive restructuring and consolidated its power through the sale of its public shares. In 1977 the first major sale was made under the Labour government. Then, in 1979, a second sale was made under Thatcher’s Conservative government. This brought the public shareholding under 50%, significant because it was the abandonment of the ‘golden share’, which granted the government power to outvote all others and veto BP’s corporate decisions. The sale was completed in 1987 with the sale of the final 31.5% stake.

The sale saw the abandonment of BP’s public facing obligation, and with this, the company shed jobs to streamline its activities. As part of its strategy of optimisation, throughout the 1990s, BP began divesting from onshore activities like oil refining, and concentrating investment into upstream activities like exploration, drilling and extraction. Divestment from oil refining and petrochemicals meant shedding onshore employment; in the first half of the 1990s, BP cut its global workforce by half, to 60,000. In Grangemouth, between 1979 and 1985, the workforce was reduced from 2,300 to 1,250, and the town’s population shrank for the first time in 1981 since its continuous growth between 1951 and 1971, signalling the impact of this deindustrialisation on the community.

BP continued to cut its Grangemouth workforce throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s. In 1998, refinery employment was brought below 1000 for the first time with 180 jobs shed. Then, in 2001, the company announced plans to cut around 40% of the site’s workforce with a staggering 1,000 redundancies. In 2004, BP made the move to divest from olefins and derivatives, resulting in the sale of the refinery and petrochemical complex in 2005 to the privately-owned Ineos. Grangemouth experienced further assaults to economic security under Ineos in 2013 with a pay freeze for refinery workers, the scrapping of the pension scheme and a ban on strike action for three years. With these economic protections abandoned, the town today experiences high rates of poverty and unemployment.

The closure of the refinery under Ineos may appear as a major shift in the industrial structure of the town. However, when situated in historical context, the proposals can be viewed as another step in a story of corporate power relations and government priorities defined by fossil fuel dependency. While the refinery workforce has been continually reduced for decades under BP and Ineos, petroleum production never ceased; even with the closure announcement, petroleum dependency will only be reinforced through the activities of the fuel import terminal.

The plans for the refinery set out by Ineos are incongruous with the demands of the climate emergency, as well as the government’s own 2045 net zero emission goal and just transition plans. There is an urgent need for government and industry to divest from carbon-intensive industrial activity, and Grangemouth, as the only oil refinery left in Scotland and a significant industrial hub, is central to this. Between now and the expected closure of the refinery in Spring 2025 there is still room for intervention into a just, worker-centred strategy for the site’s future. The town’s history serves as a reminder that it is the workers and communities – who, at the behest of the government, were placed at the heart of energy production all those decades ago – who experience energy transitions first hand. They cannot be left behind.