By James Crooks

Social media has been awash with outrage over new rules drafted by the New York City Department of Environmental Protection, which would require many of the city’s famous pizza joints to upgrade their wood- or coal-fired pizza ovens.

After an initial article from the New York Post by Marc Morano on Sunday 25 June 2023, other news outlets across the world have run with this story. On the one hand, alarmist headlines about the threat that this new rule poses to New York’s unique pizza culture have stirred up a public frenzy; on the other, unclear claims around the proposed rule seeking to reduce ‘emissions’ by 75% have led commentators to make some false equivalencies: “Green madness: You’d have to burn a pizza stove 849 years to equal one year of John Kerry’s private jet”. Even Twitter’s CEO Elon Musk took the time to weigh-in on his platform, sharing his views in a comment with over 4 million views and helping to promote the claims made by the New York Post’s original article (see Fig. 1 below).

The problem is that the claims featured in the original article – especially the title – are misleading ‘click-bait’ at best or, at worst, a deliberate attempt to manipulate readers and distract from the conversation surrounding climate and pollution regulations. Let’s take a look at what the proposed rule actually entails.

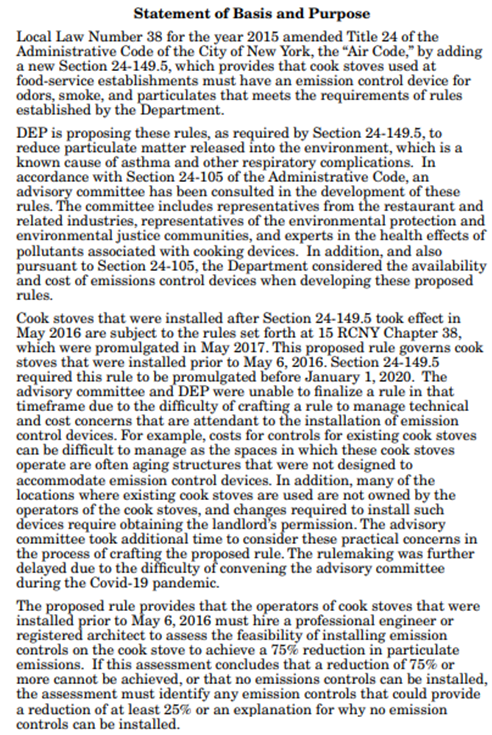

(Source: cityrecord-06-23-23.pdf (nyc.gov); page 2968)

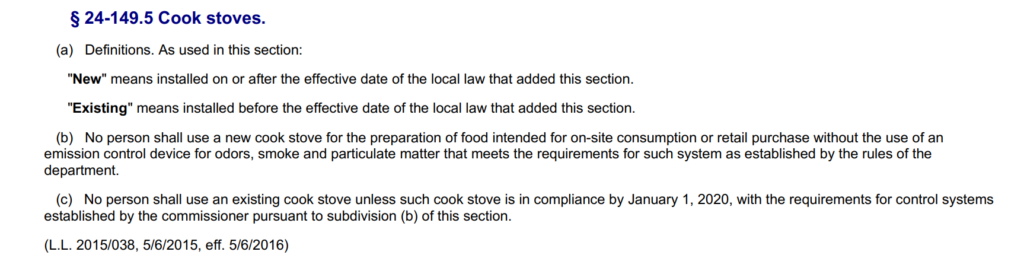

The proposed rule from the New York City Department of Environmental Protection is an addition to the ‘Air Pollution Control Code’. This code is aimed at reducing the levels of airborne pollutants in and around the New York City area. The proposed changes (see Fig. 2 above) would require food-service businesses with ‘cook stoves’ installed prior to 6 May 2016 to investigate the feasibility of applying emission-reducing devices with a target of reducing particulate emissions by 75%. This is designed to bring these older cook stoves in line with the regulations implemented in 2016 for new installations, which are required to include such emission control devices (see Fig. 3 below).

(Source: https://codelibrary.amlegal.com/codes/newyorkcity/latest/NYCadmin/0-0-0-43463).

A Cook Stove is defined as a wood fired or anthracite coal fired appliance used for the preparation of food intended for onsite consumption or retail purchase.

Contrary to the concerns raised by Marc Morano in the New York Post or echoed by Elon Musk on Twitter, this new rule has nothing to do with greenhouse gas emissions relating to climate change. This addition seeks to reduce the amount of fine particulate matter and elemental carbon in the air, both of which have been strongly linked to the development of cancer, other physical medical conditions such as asthma, as well as mental health problems including the development of dementia.

Air quality and particle pollution is a global issue. According to a 2022 study, particulate pollution resulted in the premature deaths of 238,000 people within the EU in 2020 alone. The combustion of biomass (wood) and coal is the single largest contributor to particle pollution, more so than transport or industrial combustion. Domestic combustion in the UK in 2021 contributed 27% of all particulate emissions. Local and national governments around the world are slowly waking up to the need to address particulate pollution. While heavy industry and transport have been the focus of many of these efforts, domestic combustion has also begun to come under scrutiny. Here in the UK, the introduction of eco-stove designs and regulations around authorised domestic has contributed to an 11% reduction in the estimated contribution of domestic combustion since 2019.

The need to regulate against activities, which lead to the release of these harmful particles, is made even more immediate by their localised impacts and distribution. A 2020 study conducted in UK homes demonstrated that the use of wood burners more than doubled the concentration of particulate pollution in the home, with the highest concentrations coming from ‘flooding’ events when the stove was opened. In an indoor commercial environment with an open cook stove, this becomes a significant health hazard for both staff and customers. The proposed rule in New York City seeks to regulate these kinds of environments in order to create healthier workplaces and restaurants for its inhabitants.

In a weird way, Mr Musk is right – this new rule will not make a difference to climate change. Marc Morano’s complaint that the emissions from John Kerry’s private jet in 2021 has the equivalent emissions of running a pizza stove for 849 years does seem plausible – . Local, federal, national and international bodies do need to act on a larger scale to curb harmful greenhouse gas emissions. However, as any cursory reading of the actual proposed rule change will reveal, this never really was about fighting climate change.

But perhaps neither were these articles and the various online responses.

As early as 2011, Sarah Sobieraj and Jeffrey M. Berry noted the proliferation of what they called ‘outrage discourse’ across various media platforms in the US. The hallmarks of this type of discourse are the use of sensationalism, misdirection, and misinformation to evoke visceral responses from a specific target audience. In the modern cyber-scape, which encourages ‘click-bait’ titles to maximise views and where social media allows individuals to broadcast their thoughts and opinions within echo-chambers without much fact-checking, it is perhaps unsurprising that this type of discourse has become all-too familiar – but no less insidious. Not only does the emotional nature of the reaction lend itself to being believed, the proliferation of this kind of discourse promotes the establishment of entrenched positions, which in turn undermines also the ability of a society at large to engage with and solve complex and nuanced issues.

This is a significant problem for researchers and communicators working on the modern climate emergency. The urgency of this challenge is perhaps trumped only by its complexity; indeed, the Centre for Energy Ethics was founded in order to bring discussions of the nuance and complexity of these issues to the foreground. In order to achieve any kind of ‘Just Transition’, there will need to be significant trade-offs, dialogues and engagement with and from all groups. The need for these trade-offs, while potentially self-evident to those involved, need to be carefully planned and communicated in order to deter or simply reduce its susceptibility to the ‘outrage discourse machine’. Without a conscious effort to avoid this kind of discourse, we do not just risk shouting into a void; we could be unwittingly reinforcing the already fortified positions occupied across the political spectra, creating further barriers to productive discussion and much-needed collective climate action.