By Gabriel Wigny

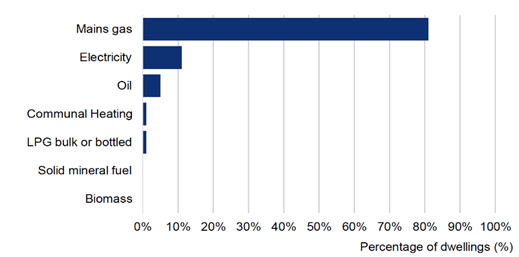

To achieve its goal of net-zero by 2045, Scotland will need to decarbonise its economy. In the housing sector, which generates 13% of the country’s emissions (mostly through heating), this means minimising energy consumption and switching to greener energy sources. However, as it stands, Scotland has some of the least energy efficient housing stock in Europe and is heavily reliant on non-green fuels (see Figures 1 and 2). With 80% of Scotland’s housing stock that will exist in 2050 already having been built, the need for retrofits is clear. But while the Scottish Government has already set aside £1.8 billion to transform its housing stock, some estimates put the required funding to achieve this at £33 billion. In this context, private finance will be essential to bridge Scotland’s significant funding gap. Therefore, this article creates an economic model to help identify possible solutions to increase the scale of investments in retrofits in Scotland’s private rented sector, which represented approximately 350,000 (or 13%) of all Scottish homes in 2022. To do this, it draws on an extensive literature review and interviews with three researchers, two consultants, an architect and a banker.

Framework

There are many options available for landlords to refit their properties. For example, double glazed windows can be installed for better insulation and lower energy consumption. Another option is setting up a heat pump, which is more energy efficient and greener than traditional heating systems. Refitted houses are generally characterized by higher Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) ratings since less energy is required to run appliances.

An important distinction is shallow versus deep retrofits. Shallow retrofits focus on individual upgrades, such as lighting or heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, providing relatively quick and inexpensive improvements in energy efficiency. In contrast, deep retrofits, represented by the Passivhaus standard in the UK, adopt a “whole building” perspective that considers the interaction of multiple systems and occupant behavior, leading to greater efficiency, comfort and long-term cost savings, albeit with significantly higher initial investment for landlords.

Better quality housing is typically associated with rent premiums because reduced energy usage will often result in lower energy bills. Therefore, the tenant’s willingness-to-pay rent is expected to increase for a house with a higher EPC rating. The amount of additional rent that tenants may be willing to pay will depend on their energy bill savings and hence expected future energy prices, as well as the value they attach to living in a warmer property.

The Investment Incentive Equation above highlights positive incentives for landlords to invest in retrofits if the sum of the discounted rent premiums is greater than the cost of the investment. Intuitively, if retrofitting costs are low, rent premiums are high and the discount rate is low, there is a strong incentive to invest.

The discount rate is the rate of interest that a landlord would be charged on any money they borrowed to fund property improvements; or the rate of interest they could have earned on any of their existing funds that they put towards the upfront investment costs of retrofitting (for the purposes of this analysis these two interest rates are assumed to be the same). If the discount rate is high, investing in energy efficiency is more expensive and landlords might find that they are better off lending their money instead. In contrast, if the discount rate is low, borrowing is cheaper and retrofitting may be more attractive than lending.

However, this equation does not capture how changes in property value after retrofitting affect the incentives of private homeowners to invest. Whilst this is outside the scope of this article given the six-week period available to investigate this topic, studies have found that retrofits increase property values, strengthening the incentives to invest as the upfront cost can be recouped by selling the property at a higher price. With this framework in mind, the next section of the article underlines some economic hurdles that constrain investments in the private-rented sector.

Hurdles

Low Rent Premiums

The first hurdle is that rent premiums are weakly responsive to improvements in energy efficiency. Studies have shown that energy efficient homes can increase rent by 2% to 11%. Nevertheless, landlords do not benefit sufficiently from higher rents after the retrofit to offset the cost of the investment, diminishing investment incentives. For instance, a 2% or 3% return on these investments is not enough to cover the upfront cost. To illustrate this point, a landlord in Scotland typically spends £30,000 on retrofits and in return sees a monthly rent increase of just £150, with a payback period of 16.7 years. Indeed, the Green Heat Finance Taskforce found that “retrofitting measures [are] seen as ‘nice to have’ but are not fully reflected in valuations.”

A key factor here is the “split-incentive problem” between landlords and tenants. This problem suggests a cost-benefit asymmetry, whereby tenants benefit from lower energy bills and landlords incur the cost of the investment. It is in the tenant’s best interest to live in a well-insulated house because they will benefit from lower running costs. In theory, some of their savings resulting from improved energy efficiency could be transferred to the landlord via a rent premium. However, in practice, current UK legislation imposes significant limitations on the potential of variable rent structures and the sharing of energy savings. Under a tenant-pay regime for utilities, landlords cannot recoup the value of their investment as the savings from lower running costs do not materialise into premiums. Therefore, the lack of financial instruments that can distribute savings more equally causes landlords to underinvest in energy efficiency.

Furthermore, the monetary return on energy savings is low because electricity currently costs close to four times as much as natural gas per kilowatt hour in the UK. For the typical Scottish home with a low EPC rating and gas heating (see Figures 1 and 2), decarbonisation requires a retrofit to improve energy efficiency and switch primary heating fuel from gas to electricity. However, in this scenario, since retrofit-induced energy savings may be swallowed up by higher energy bills, little money is freed-up for the tenant to pay a premium. In turn, this makes it harder to convince landlords to make these improvements in the first place. A report by Energy Systems Catapult shows that low confidence in energy savings is a key barrier that prevents many households from taking steps to decarbonise their homes.

In fact, there is evidence that the “price structure of the UK electricity market (…) [leaves Scottish] homeowners in a relatively worse financial position” after retrofitting their homes. This is because the UK electricity market uses a clearing mechanism where the last generator to meet electricity demand sets the price for all generators. Often, this “marginal generator” is a gas plant, which can quickly adjust output (unlike inflexible weather-dependent renewables, gas plants can meet sudden demand spikes). As gas prices have soared with the Russia-Ukraine war, so have electricity prices, even though many generators produce electricity at much lower costs (see Figure 3). Additionally, fossil fuels subsidies are making it harder for renewables to compete price-wise, which complicates the push for net-zero housing.

Asymmetric information also affects the responsiveness of rent premiums. Tenants searching for a new home know that different dwellings have different levels of insulation, yet these differences are costly to observe. For instance, a renter analysing a set of different dwellings may know that there is a distribution of window insulation quality and hence of resulting heating costs. Typically, the running costs of heating will be known only once the home is occupied. However, as a result, tenants will not be willing to pay a rent premium for better energy efficiency before having tested it. Although asymmetric information remains an underlying problem, the consequences are less important in Scotland because EPC ratings provide a rough estimation of energy savings.

High Costs

In most of the interviews conducted for this article, the high cost of retrofitting was referred to as the biggest obstacle towards its implementation. Retrofitting a standard Scottish house can cost up to £100,000, depending on the place and the work it needs. In the Investment Incentive Equation (Equation 1), this corresponds to the costs (left-hand side) being greater than the discounted rent premiums (right-hand side). As the architect interviewed stated: “People are not interested in deep retrofits because it is so expensive.” Instead, people invest in shallow retrofits that make their house more comfortable but not carbon neutral. The heterogeneity of Scotland’s housing stock contributes to this challenge. Different types of homes, each with unique characteristics and tenureship contracts, require tailored retrofits, which complicates the large-scale implementations of these improvements to achieve economies of scale.

However, heterogeneity alone does not fully explain these high costs; spatial distribution and transaction costs, such as complex paperwork under PAS2035 guidelines, also contribute. PAS2035, the official guideline for retrofits, is often criticised for being overly complicated because many pages need to be completed using technical terminology and various experts need to be contracted to coordinate the implementation of the retrofit. In an interview, a net-zero consultant referred to PAS2035 as “a bureaucratic solution to a technical problem” and pointed to it as the main reason people hesitate to invest in deep retrofits.

In addition, this consultant claimed that the absence of centralisation and guidance in the retrofitting process deters landlords from investing. Indeed, vague information around changes to EPC legislation has left landlords uncertain whether to improve now or wait for exact details and potential technological advancements that might make retrofitting cheaper in the future. Investments are further discouraged because information is distorted by interest groups who spread misinformation regarding the potential drawbacks of retrofits.

The challenge of high costs is also amplified by behavioural biases such as loss aversion. When facing risky monetary decisions, actors place more weight on potential losses in comparison to potential gains of equivalent monetary value. Consequently, landlords may be reluctant to invest despite the long-term benefits for themselves and society.

Low Supply of Finance

The last main hurdle to retrofitting is the low supply of finance at competitive rates resulting from the perception of the retrofitting sector as being highly risky. Potential changes in national policies add uncertainty for financiers and the new market for energy efficient housing retrofit has yet to demonstrate strong demand. As one researcher interviewed stated: “There is no easy way to capture the monetary value of renovations and transform it into a revenue stream to provide a return to investors.” This is particularly challenging considering the size of individual investments in home retrofits is much smaller than preferred by investors. The researcher added: “Each one of those individual transactions is big for the person doing it but [from the financiers’ perspective] these are small-scale investments with high transaction costs.”

While securitisation (debt pooling) could address this issue, it raises concerns about tradability and liquidity (the ease with which an asset can be converted into cash without affecting its price). The 2008 financial crisis caused reluctance to explore this path because it triggered similar problems. All this uncertainty dissuades financiers from developing new financial products geared towards net-zero housing. For instance, many interviewees pointed out that green mortgages (mortgages that provide preferential terms when the buyer demonstrates that the property being financed meets specific environmental criteria) are rare, mostly limited to new builds with specific EPC ratings and seldom available for retrofits. The lack of competitive financial products for retrofitting hampers the ability of landlords to secure affordable finance. As illustrated in the Investment Incentive Equation, a high discount rate makes future energy savings look less attractive, which means long-term investments are not as tempting.

Solutions

To enhance energy efficiency, establishing a network of local one-stop shops is a promising solution. These hubs would guide households through retrofitting by providing end-to-end support, reducing transaction costs and increasing information accessibility. By making the process more straightforward, landlords are likely to see the value in energy efficiency. Such a program was successfully implemented in Ireland with the number of homes undertaking deep retrofits rising by 108% in a single year. The key here is centralizing the retrofitting process and making it as smooth as possible for landlords.

Another essential approach involves reframing the narrative around energy efficiency to emphasise personal benefits rather than solely environmental ones. Highlighting the advantages of better insulation (such as noise reduction, fresher air and consistent indoor temperatures) could redirect some of the £28 billion spent annually on UK home improvements toward decarbonisation. Households must understand that retrofitting their homes is good for both the planet and their health, but most importantly their health. Currently, people still fail to make the link.

Moreover, lobbying Westminster to restructure electricity markets will be crucial to increase investments. As explained earlier, the single market electricity price for “all market participants” in the UK is based on the last and most expensive electricity supply bid available to meet demand. This pricing mechanism has led to high electricity prices, slowing the electrification of heat. Beth Howell, an environmental journalist, argues that Scotland could address imbalances in energy costs by bargaining and emphasising that it produces most of the wind power in the UK. In fact, wind power has emerged as the UK’s primary source of energy and it is one of the cheapest sources of energy. Another alternative proposed by Sean Field, Director of Policy at the University of St Andrews’ Centre for Energy Ethics, is to set the electricity price by calculating the total weighted average cost of electricity supplied to the grid, rather than setting the price based on the last most expensive supply bid. Redefining the pricing mechanism for electricity is important as low electricity prices will be critical to ensuring a timely, just and equitable transition to a low-carbon society.

Implementing area-based retrofits across social housing projects is also crucial to build investment confidence in the private sector. Ken Gibb, a Professor of Housing Economics at the University of Glasgow, argues that social housing offers a testing ground for larger retrofits, helping to establish best practices. Scotland’s tenement buildings provide a critical test case, as they are old, diverse in ownership and difficult to insulate, yet central to urban housing. A pilot project in Glasgow, for example, applied an EnerPHit (near-Passivhaus) retrofit to a pre-1919 tenement. Although costly, the retrofit achieved significant reductions in energy demand and fuel bills. Importantly, such examples are a first step towards building confidence of private sector landlords who may invest if they see the economic benefits resulting from deep retrofits.

Finally, financial innovation will be central. Scaling blended finance (using development finance to mobilise private capital) through the Scottish National Investment Bank (SNIB) would unlock early market investments. Acting as a patient investor with a long-term investment horizon, the SNIB can de-risk projects and signal confidence to private investors. The banker interviewed argued that mixing public and private funds could encourage landlords to invest because the involvement of a major investor such as the SNIB would create a perception of long-term stability. Indeed, even if the retrofitting market suffers from short-term volatility, the SNIB’s long-term financial commitment would remain.

Conclusion

This article’s main contribution is in addressing a specific challenge within Scotland’s broader climate change objectives – decarbonising the private rented housing sector – and revealing just how complex even this narrow focus can be. This study identifies three major barriers to investment: low rent premiums, high retrofitting costs and limited supply of affordable finance. Although the range of interview data is limited, it provides key insights into the economic hurdles that constrain investment, as well as potential solutions for overcoming them. These include establishing a network of one-stop-shops, reframing the narrative around retrofits, restructuring the electricity market, leading the way with social housing and scaling blended finance to crowd-in private capital.