I was asked to write something for the University’s online annual Burns Night on 25 January, responding to Burns’ views on environmental issues.

You can watch my filmed reading again here, with my notes below – on how I approached the invitation, and of course, the poem that came out of it.

To speak of endings

after Robert Burns

I

If we’re to speak of endings (of which I know I’m

part), since we’re inventing instruments that truly

can recalibrate the means of our existence, then sorry

is a start. To reconcile that hu-man’s

impulse to out-fox a false dominion

may be timeless, is time-limited; has

us girded, digging with a broken

blade amidst this age of great repairs, as nature’s

own upending reason gilds a nascent social

season – rising to a truer union.

II

A start’s a start, for a’ that. I’m

sore aware that one side’s fate is truly

ill-equated with the other, and that this sorry

state betrays the pillars of the mans-

ion. Can we rebuild without dominion

in our minds, those crooked lines that has-

ten degradation? Whose broken

bones lay bare in nature’s

separation, here restored as social

equals, rooted in re-union.

‘To a Mouse’ was recently voted Scotland’s favourite poem in a VisitScotland poll.

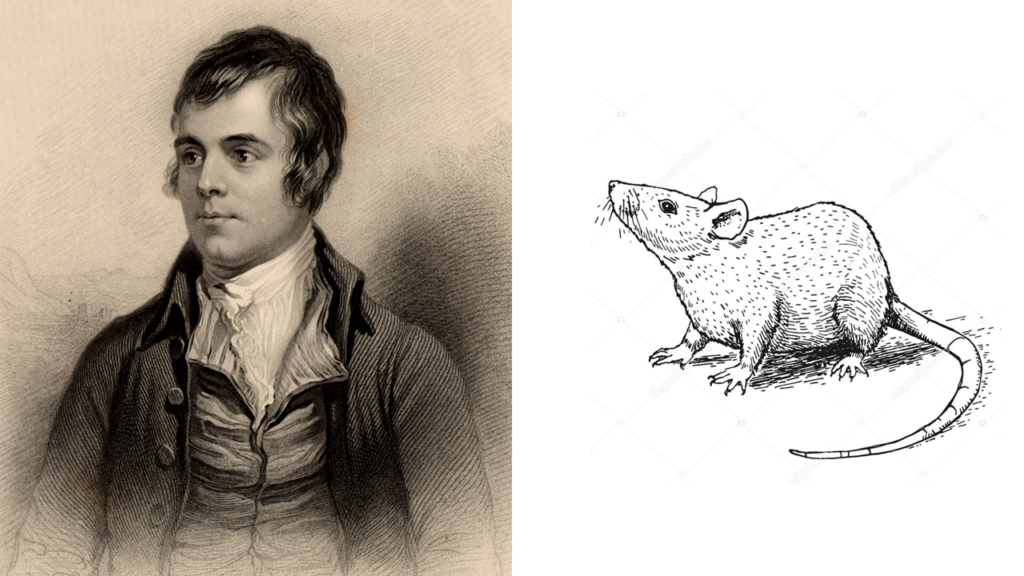

Burns wrote widely about our relationships with nature and the environment. As a farmer, he had intimate connection with his natural surroundings, and a keen awareness of the effects of human intervention, always acknowledging and usually lamenting his own complicity. He was an early advocate against cruelty to animals, writing clearly and powerfully on our treatment of the environment and other species, connecting to wider ethical and political views.

I’ve written a poem in the style of a Golden Shovel. The Golden Shovel form was created in recent years by the American poet Terrance Hayes, in response to the work of another great American poet, Gwendolyn Brooks. In this form, you take a line or a phrase, sometimes more, from another poet’s work. You then use each word from that phrase kept in the original order, as line-endings in your own poem. The main effect of the Golden Shovel form is to celebrate and pay homage to another poet – and of course, Burns often paid tribute to other writers within his own work.

And a quick technical aside: using a form for a poem can really help when having to write something quickly to a deadline! It gives you a template and some useful restrictions. It can then feel a bit like solving a puzzle, which I find can help loosen then organise your ideas more than if you had a completely blank canvas. (Sometimes…).

In choosing a line of Burns’ to quote for themes of the environment, I could have drawn from several: there’s On Seeing A Wounded Hare, or On Scaring Some Water Fowl in Lock Turit, or To a Mountain Daisy, all of which demonstrate Burns’ strong views on humankind’s impact on the environment and on those more vulnerable than ourselves.

But for a quote to have that desired impact, I’ve chosen from arguably his most famous poem on this subject, To A Mouse (On turning her up in her nest with the plough). The first two lines from the second stanza:

I’m truly sorry man’s dominion

has broken nature’s social union,

I’ve woven those lines into my poem – each word placed at the ends of my lines. The purpose is to pay tribute while also carrying the ideas forward into something new. To A Mouse ends rather bleakly, with Burns in 1785 bewailing dreary prospects and fear for the future. Here, I present a somewhat more positive and proactive outlook, all things considered. And I’ve done it twice – that is, repeated across 2 verses: as a nod to Terrance Hayes’ original poem The Golden Shovel, after Gwendolyn Brooks.

My own title To speak of endings is also a sort of nudge and a wink to the reader to look out for those end- words…