A lot of my thinking continues to be around our relationships to change, safety, un/certainty and risk in the face of climate emergency; and where these terms become highly subjective. Also around memory, imagination and time, as we sit on a hinge looking both forward and back.

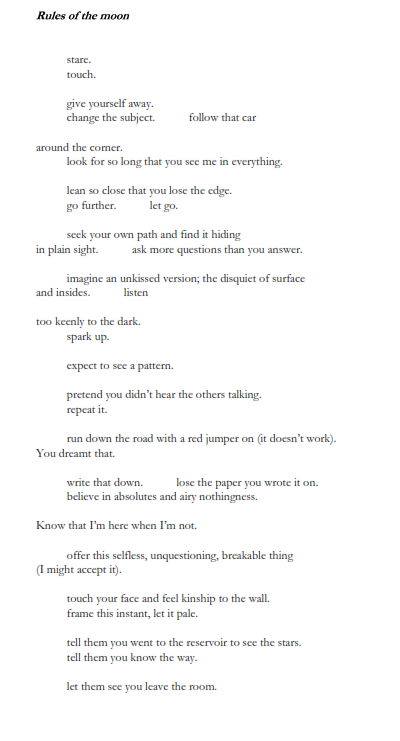

Rules of the moon is an existing poem of mine, previously uncollected, which I intend to include in the new body of work. Presented as a set of ‘rules’, the poem almost immediately strays from the brief. It formed the nucleus of a performance of the same name, which I created in collaboration with composer and sound artist Philip Jeck. We first performed it together at The Bluecoat, Liverpool in 2013, supported by Arts Council England; and subsequently at Leith Theatre as part of Hidden Door Festival in 2017.

The full performance text (live and recorded) took the point of view of an unreliable narrator, exploring false memory and the multiform story. Both poem and performance stem from a false memory I’d held onto for an embarrassingly long time, from the experience of a fire at my childhood home. I’d remembered that all the neighbours had gathered in the street (true), and that one neighbour had put on a red jumper and gone running down the road waving her arms in order to get the fire engines to come (not true). This idea of rules – what one does to get the fire engines to come – then becomes a shimmering thing: an exploration of what was made up in the dark, a long time ago.

The poem is semi-concrete, with a recurring gap of the same size suggesting a missing word – the same word throughout (you’ll be told in a moment what the word is, so pause here if you want to take a guess). In these luminous spaces, the hesitancy or uncertainty they may provoke – lit by memory, fantasy or guesswork (or indeed, by the moon) – the poem invites questioning around our human impulse towards fixity, structure, certain rules and notions of what stability looks like. Perhaps unsurprisingly, glimmers of subversion and absurdity also live here.

As a thought experiment, if we were to fill every gap with the same word – Don’t – we’d see a very different set of instructions, the opposite in fact. The very manifestation of negative space. Other words may fit, of course – but don’t is the one you’re getting, since most lists of this ilk are compiled of Dos or Don’ts.

Fans of technical detail might enjoy that the word is there, typed each time in black then turned to white – partly for poetic completism, and partly to ensure the gaps are consistent (and that they don’t shift in digital transit – something interesting there about my desire for fixity).

Thinking again of those gaps as they were ‘before’ – before we were told the ‘secret word’, or before we even considered anything was missing. Those bright omissions, those intakes of breath – perhaps now they might seem less ‘hesitant or uncertain’, but something else instead. After all, how much can we ever truly know of the moon’s intentions? I like to imagine that of all astronomical bodies, the moon is the one most likely to keep something back. What we once felt as an absence might now look like a boundary – or in the sense of something having been occupied or extracted, a wound.

Of course, the poem itself doesn’t tell you what I intended the missing word to be – nor does it need to.In usual circumstances the reader is left to wonder, which carries its own effect. But since we have this time together, let’s consider:

- do you find yourself longing for that absence (of ‘knowing’; of Don’t)? Or if there even is a longing, what is it for?

- Do you feel… nostalgic, bereft, exhilarated, relieved, hoodwinked, opportunistic, defiant, territorial, vengeful, on the winning or the losing side?

- What does this knowing do to your memory of the way things were ‘before’?

- What has been broken; or what if anything, has been ‘fixed’?

- What else do you feel? What’s changed, what’s new?

At the end of the day, of course the moon brings its own, entirely crucial rules – of time, gravity, tides, and of wider astronomical relationships. Poetically too, the moon rules our dreams and fears; our subconscious, our instincts, emotions and imaginations; our feelings about comfort, intimacy, identity, and belonging. The language of the moon is in eclipses, waxing, waning, halfway hinges: it’s in doublespeak, metaphor, homonym, antonym and oxymoron. We perceive the moon only by what it reflects back to us: sunlight, ourselves, a version of events. Presented with this imagined voice of the moon as an unreliable narrator; by suggesting that negative space isn’t speechless, what we might hear if we listen closely, is – Says who? (The missing word is only Don’t because I told you it was, after all. Don’t just take my word for it.)

For whom does the poem speak? To what end? Who stands to benefit from these, or any rules? What does the silence tell us? And what then is the role of our re-membering, reimagining; unlearning, forgetting, retelling? If memory is subjective, so too the future must equally be up for grabs – when darkness falls, and dreams are in the driving seat. How do we know when we’ve got things right? And how do we recognise when it’s time to risk the script?

…

You can hear the poem here, extracted from the recordings for performance composed by Philip Jeck.