By Sarah O’Brien

“Those of us on Government benches believe in jobs, not mobs”[1]. It was with these words that the then UK Clean Growth and Energy Minister Claire Perry addressed the House of Commonsin November 2018. The Minister announced she would visit a controversial shale gas site in Lancashire to meet those “exploiting the resource to create jobs” as well as those opposing the site. Jobs versus mobs; this was how she framed the situation on the ground. Perry’s polarising words fuelled an already divisive situation, directly positioning those challenging the hydraulic fracturing (also known as ‘fracking’) for shale gas as against the creation of jobs. This framing simplified their concerns about the industry as well as their relationship with work and employment.

At the time of Perry’s comments, anti-fracking campaigners had been firmly standing their ground against the development of the unconventional gas industry in the UK. Since January 2017, when the construction of the Preston New Road (PNR) site in Lancashire began, some had maintained a daily physical presence on the roadside. Peering out the window in a passing vehicle, clusters of people and placards could be seen dotted around the entrance of the site, more often than not accompanied by lines of police officers in high-vis jackets.

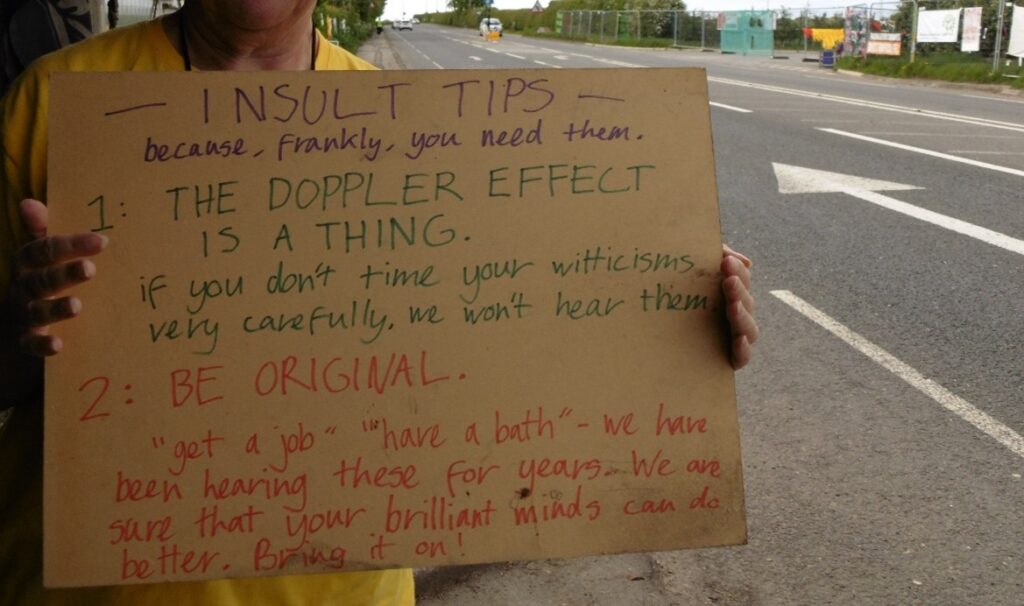

Staying on the bus to Blackpool, you could be left with that image and wonder why people were spending so much time on the side of a busy A-road. Sometimes frustrated drivers would angrily shout out their window: “Get a job!”, echoing Perry’s framing of a “mob” versus “jobs”, or her description of campaigners as a “travelling circus” earlier that year during an address to Members of Parliament.[2]

Rather than staying on to Blackpool, I got off the bus in December 2018 to start fieldwork. However, I did not find a mob nor a circus. The campaign, which had formed on the side of the highway, was sustained by and feeding into a broader network of concerned residents. As I came to learn, it was a bright mesh of friendships, conflicts and hardships.

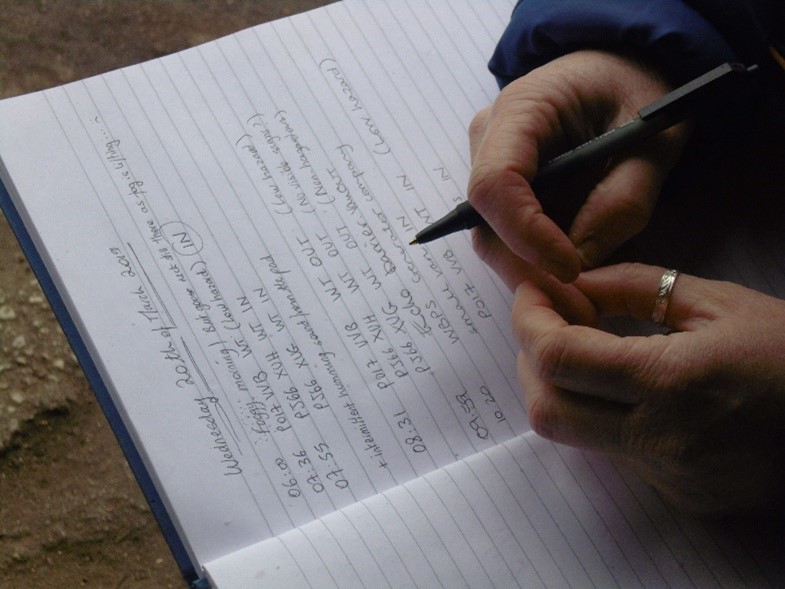

The combined work emerging from the campaign was humongous and many activists described themselves to be “living and breathing” this campaign. There were those working on their computers, navigating complex legal and technical domains. Others were spending days on the roadside physically monitoring the site and resisting the equipment being delivered to it. Some were arranging interviews and writing press releases, self-taught videographers were editing hours of videos to document the protests and the policing, and still others were preparing and providing basic food and other practicalities to sustain the campaign.

Journalists and visitors invariably asked the campaigners: “But how do you make a living?” This concern about employment seemed to be the elephant on the road. Pensions, savings, a full-time job, a part-time job, freelancers, benefits, students; the movement had attracted people from a variety of backgrounds and circumstances. Most of the activists who were not in salaried employment when I met them and who were not of retirement age had fully thrown themselves into this campaign. They spoke of their involvement as if they had a job – a controversial job with no wages, no stability, no prospects of promotion, and with the added feature of being under close surveillance by police officers. A job with research to do, with time-pressures to live by, with shifts to accomplish and with teams to work with. A job which attracted both admiration and stigma – partly because it meant those undertaking it were not part of the formal labour market and had to rely on the support of others for many aspects of their lives. One of my interlocutors, who lived on the resistance camp close to the site, would often joke: “I have taken the activist vow of poverty!”

As I came to experience during my fieldwork, working in this way was definitely not easy. The practical and emotional solidarity that was central to this kind of grassroots movements came with inevitable tensions and interrogations into the value and efficiency of certain protest activities. Yet it also meant people forged bonds through adversity, learnt from one another, and worked together to support each other’s aims and livelihoods. They were questioning their own notions of valuable and meaningful work outside of formal employment. In this way, the work of anti-fracking activism was a collective as well as a personal and intimate endeavour.

Whether formal employment or otherwise, work carries significance in relation to the local economic and historical context in which it is carried out. One dedicated anti-fracking campaigner told me: “I don’t blame them, you know, it’s hard to find work around here”. She was talking about the security guards working on the site. She reflected: “There is a lot of work to do, but there are no jobs”.

Throughout my fieldwork, I came to learn about some of the historic changes experienced by the “Desolate North”, particularly the North West and the areas around Blackpool and Preston.[3] I was told of the once-thriving textile industry around Preston, the loss of the fishing industry in Fleetwood, the decrease and eventually end of the activities on Preston Docks, as well as the dwindling tourism and investment into Blackpool. The people and the natural beauty of local areas were something to be proud of – yet in the same breath, I would be told of how Blackpool ranked high on various official measures of “deprivation”[4].

In this context, the prospect of job creation attached to the onshore gas industry could be a great opportunity for Lancashire, a region which “has for centuries had first- or early-mover advantage in nascent industries.” [5] The hope for many, including Claire Perry, was to build on the industrial potential of the North and create a skilled labour force that would lead the way in UK onshore extraction.

Organisations such as Friends of the Earth (FoE) pointed to the same arguments: the need for employment in the northwest and the creation of a skilled labour force. But they did so in order to challenge the industry and urge the government to shift focus to the renewable energy industries instead. FoE questioned the predicted employment figures that were mentioned in pro-industry reports. They emphasized the inconsistent numbers put forward, the short-term nature of the work, and the potential damaging impacts of the shale gas exploration on other valuable sectors.[6]

The FoE campaigners and the anti-fracking campaigners whom I met during my fieldwork were worried about the land, the water, the air, the changing climate, the depreciation of house prices, to name but a few. In addition to this, campaigners considered shale gas plans incompatible with international agreements and reports calling for long-term systemic changes in “energy, land, urban and infrastructure”.[7] For them, developing this industry would be “locking” the Northern regions into capital-intensive infrastructures that would extend the life of fossil fuels beyond necessary, to the detriment of other energy sources and other projects that could benefit local communities.

The people I met were therefore not interested in employment for employment’s sake. Given the scale of the transition as urged by the IPCC reports, and the environmental impacts of the shale gas industry they did not just believe in jobs, to pick up on Claire Perry’s words. Rather, the work of activism that they took on by opposing the shale gas industry called into question notions of valuable work and desirable employment. What is worth spending time on and what are people’s livelihoods worth?

Their work as protesters was thus a way of holding industry and government to account in this transition. It was not a way to prevent people from making a living. As they found ways of working together, they were forced to look at their personal situations, projects and activities in relation to the energy infrastructure they were fighting against. They were asking themselves not only what kind of energy is appropriate to fuel our societies and our work, but also what kind of society and work we want to fuel.

[1] As reported by Ruth Hayhurst here https://drillordrop.com/2018/11/20/energy-ministers-promises-to-visit-anti-fracking-protesters/

[2] See a video of Claire Perry as she addresses Members of Parliament – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=muD9SndVDVU

[3] The “Desolate North” became a reclaimed slogan for many of the campaigners I met. In 2013, a Conservative peer used the word to describe areas in the North East he thought could be suitable for fracking purposes, as they were supposedly less densely populated and with did not have any particular natural features to preserve. See https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-23505723.

[4]These indices serve to measure different levels of poverty across the country. See “The English Indices of Deprivation 2019”. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/835115/IoD2019_Statistical_Release.pdf

[5] See the pro-industry reports “Getting ready for UK shale gas” http://www.groundgassolutions.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Getting-ready-for-UK-shale-gas.pdf and “Getting shale gas working” https://www.iod.com/Portals/0/Badges/PDF’s/News%20and%20Campaigns/Infrastructure/Infrastructure%20for%20business%20getting%20shale%20gas%20working%20report.pdf?ver=2016-04-14-101231-553

[6] See FoE report “Making a better job of it” https://friendsoftheearth.uk/sites/default/files/downloads/making-better-job-it-full-report-75291.pdf

[7] See p.17 of the IPCC’s special report in 2018 on “Global Warming of 1.5˚C”