By Anna Rauter

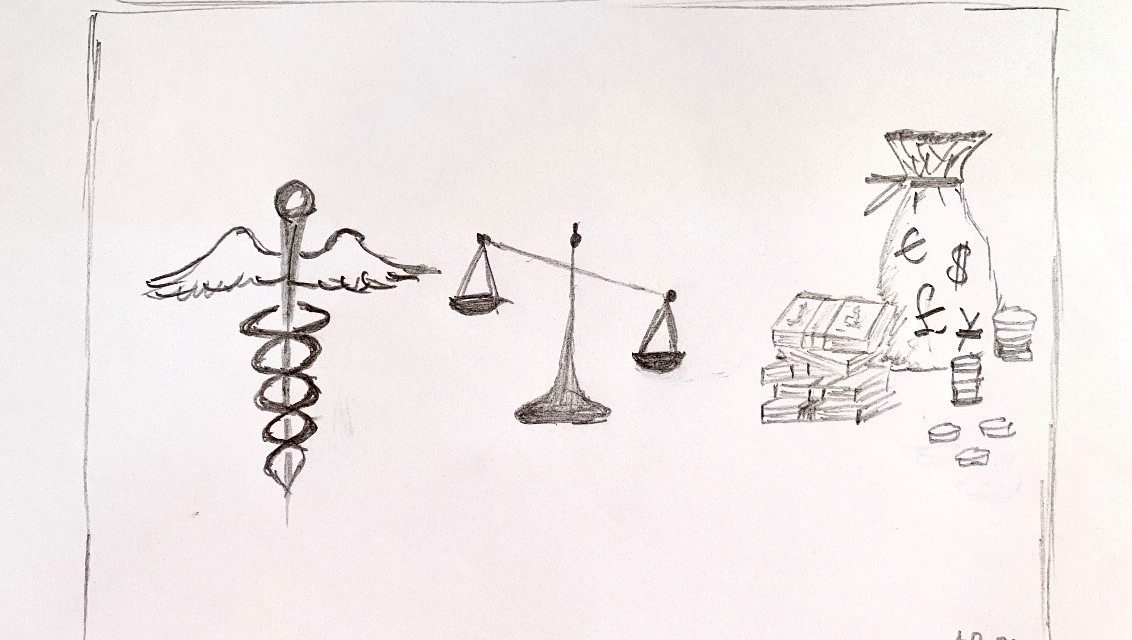

Health and safety of the population first. Economy Second. This has been the motto for most countries around the world following the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. But whilst many political leaders appear to prioritise the health of citizens over economic growth during this pandemic, why have they not prioritised the health of the planet over economic gains in the face of climate change? Is there something that makes saving human lives more valuable than protecting the lives of humans plus the flora and fauna of the planet we live on? When are market economic gains worth sacrificing?

The world is currently being confronted with two global crises[1]: the ‘climate crisis’ and the ‘coronavirus crisis’. These coinciding phenomena of global magnitude provide a unique opportunity for analysis, and ultimately elicit the question: why is one handled so differently from the other?

Whilst climate change and the coronavirus may seem like vastly different issues at first sight, they do have one crucial aspect in common: both are ‘phenomena’ which have not been witnessed by humans to this extent before. Whilst there have been economic downturns, stock market shocks, various viral outbreaks, and natural disasters, none of them have hit quite the global magnitude of climate change or the coronavirus outbreak. When crises resemble a previous event, we can draw on past experiences to make sense of the now and to guide us into the future. These two crises are however accompanied by a lack of experience and high degree of uncertainty.

So, what is different about the two crises – and can this help us understand why there has been such a strong, decisive action against one but not the other?

One defining difference between the two crises is the way they are perceived. Let us for example examine how the World Health Organisation (WHO) frames the crises; “the COVID-19 pandemic is a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), which has claimed lives, and severely disrupted communities. Climate change is a gradually increasing stress that may be the defining public health threat of the 21st century” [my emphasis]. This statement represents two drastically different valuations of the crises. While the coronavirus pandemic – a “health emergency of international concern” – evokes the image of a hazardous, immediate threat to personal safety and health, the portrayal of the climate crisis as a “gradually increasing stress” elicits merely the sense of a distant worry.

In Norway, I have had many conversations with my interlocutors about climate change perception. I was told of studies that marked Norway as one of the few countries that would be the least adversely affected by changes in the climate. As such climate change was not an urgent worry for personal safety for most of the people I interacted with, but rather a distant ethical or philosophical concern. In other places around the world – those affected by droughts, rising sea levels, freak weather – climate change is without a doubt perceived as a pressing issue in need of immediate action. It must be noted that the people I have interviewed by no means underestimated climate change in significance, and many of the experts and leaders I have met take an active role in developing and supplying energy and climate solutions. However, most of these solutions are tied to economic incentives and market opportunities. The idea that a crisis could be dealt with outside and irrespective of market economic structures seems to be absurd or naïve to most leaders – but perhaps COVID-19 can help change this perception.

The deep sense of immediacy that has been evoked by the coronavirus pandemic has led leaders to prioritise health and safety over economic activities. With that, COVID-19 has demonstrated that market economics do not trump everything. Media, experts and politicians alike have cited “ethics” and “morals” – protecting the weak, showing community spirit – as the pillars of getting through the coronavirus crisis. As such, the pandemic seems to prove those wrong who assumed that economic value maximisation is the overarching impetus for our 21st century globalised lives. Still, I wonder – why is this realisation only emerging with the outbreak of a global pandemic? After all, climate change has been recognised as a problem (or indeed as a crisis) long before the current coronavirus was even born?

Climate change (for now!) is not as egalitarian as the coronavirus. It currently affects some areas more than others, which often coincide with marginalisation, and economic inequality. The COVID-19 pandemic, unlike other crises, is not localised to a specific region that can be ‘treated’ at a distance with aid packages from unaffected areas. It is a disease that very much affects all including the privileged. As such, it is perhaps one of the first times in global world history where both the rich and poor are simultaneously threatened by a crisis (this is not to say that everyone is equally affected. There are of course vast differences in accessibility to health care, as well as other socio-economic and political dispositions. The COVID-19 pandemic – just like climate change – may ultimately further global economic inequalities[2]). It is this mass-perceived immediate and simultaneous personal threat that affects everyone including powerful decision-makers, which has led to prompt, decisive action. Other crises, like climate change, which are perceived as more distant – particularly to the privileged and powerful – are not treated with the same urgency.

Importantly however, the COVID-19 responses allow us crucial insights into what a crisis response can look like. The decrease in the consumption and production of goods and services as a result of the coronavirus pandemic measures has led to a momentary drastic decrease in greenhouse gas emissions. While emissions are expected to rise again as market economic activities resume, COVID-19 has demonstrated that people – most importantly leaders – are willing to sacrifice economic activity for the good of society – as long as the perceived threat feels immediate enough. The trump of non-economic concerns over market economics marks a historic moment in time and can give us hope that this can happen again in the future with other crises – notably climate change.

[1] Crisis in this article is defined as: “a time of great disagreement, confusion or suffering” (Cambridge Dictionary).

[2] See study by Diffenbaugh and Burke 2019: https://www.pnas.org/content/116/20/9808