By Gard Frækaland Vangsnes

In late March 2025 the international gold price surpassed the milestone of 100 US dollars a gram. At the turn of the millennium, it was 9 dollars a gram. In comparison, the average annual inflation rate of US dollars between 2000 and 2025 was at 2.5% which means that average commodity prices in US dollars are 1.86 times higher today than in 2000. There are, of course, different factors impacting currency and commodity prices, but the marked increase in gold prices in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and Covid-19 exhibits its correlation with geopolitical tension and market uncertainty – when everything trembles, investors turn to gold.

Moreover, as the anthropologist Elisabeth Ferry notes, in contrast to other commodities, gold represents itself; it does not (only) signify value, it is value. In essence, this means that anyone in possession of gold, everywhere on our planet and whensoever (at least across the last four millennia) holds what Sherry Ortner called a key symbol. According to Ortner, key symbols attract and condense large amounts of meaning which shapes cultural particularity. Gold as a key symbol, however, not only works within cultures, but across spatial and temporal difference on a global scale. Since value is not merely a question of supply and demand, but fundamentally about how people afford trust and beliefs to objects, the monetary exchange value of gold tends to increase with social unrest.

Most of global gold production stems from large-scale mining (LSM) projects while so called artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) accounts for around 20-30%. Nevertheless, a major concern in the context of skyrocketing gold prices is the deepening and widening of ASGM activity throughout the world, especially along the tropical belt. Whilst inherently hard to measure, the global ASGM community counts between 20-30 million people. These are probably conservative numbers since they rely on surveys published in 2019-2020 that fail to consider the last boom in gold prices. At any rate, the inclusion of people who are indirectly involved or (partly) reliant on the ASGM economy, increase this number many fold.

There is certainly a lot to be said about the intricacies, scales and modalities of gold production, let alone a deep history of a peculiar human fetishism. In this blog post however, I want to turn our attention to the expansion of ASGM in the Amazon and some specific developments that may be familiar to some readers while surprising to others.

The Amazon basin is arguably the world’s most important forest given its capacity as a carbon sink and its role in the hydrological cycle. Life abounds in these forests, biodiversity levels and magnitudes are unparalleled alongside a significant cultural, ethnic and linguistic diversity. People living there struggle however, increasingly, to maintain a place to live and eat, and to make ends meet. Indeed, indigenous groups have battled with colonial pressures for five centuries – they are born and raised in this struggle. And yet, the current scope and scale of predatory capitalism both in its legal and illegal guise, is unprecedented.

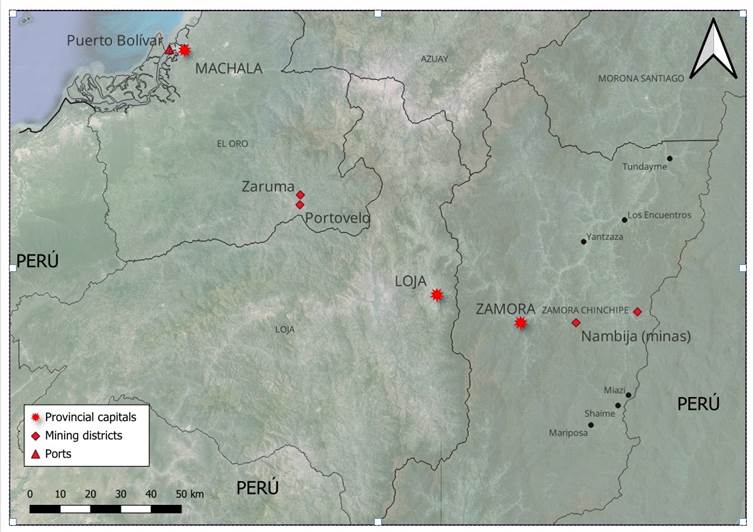

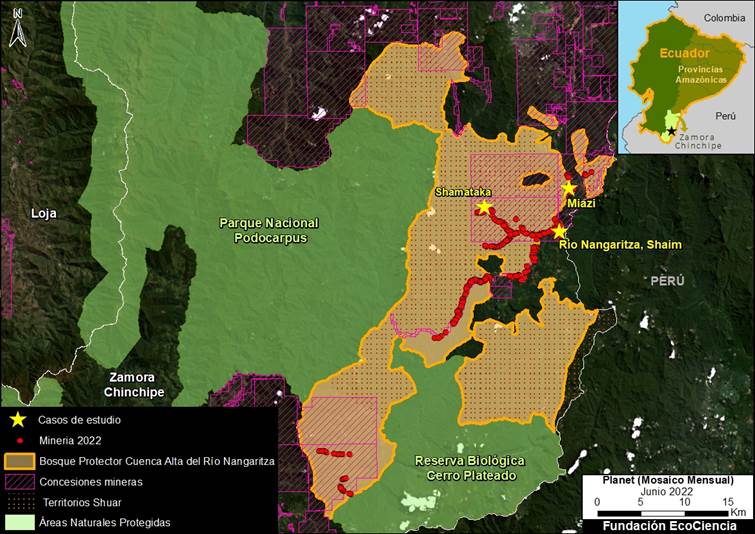

Since 2017, I have followed the expansion of gold mining in the southeastern Amazonian corner of Ecuador, in a province named Zamora Chinchipe. In many aspects, the story of gold mining here echoes similar developments in other remote corners of the world; a story that begins with European colonizers’ obsessive search for this precious metal, followed by settler colonialism, encroachment of indigenous territories, the arrival of international mining companies and lastly, a consolidation of gold mining as a coexistence of LSM and ASGM. Indeed, it can be argued that gold fever is a latent risk regardless of context, but what stands out in the case of Zamora Chinchipe is a recent shift from indigenous resistance to indigenous engagement with gold mining.

In 2017, the Shuar communities of Alto Nangaritza, a relatively remote area along the border between Ecuador and Peru, decided through a majority vote, to open their territories to external gold miners in exchange for a percentage of retrieved gold (normally around 15%). Shuar communities in the lower slopes of the Nangaritza river had already begun washing their lands for gold from the turn of the millennium, but this was an isolated case, often criticised by neighbouring Shuar communities. Contrastingly, the Shuar turn to gold in 2017 sparked a regional gold rush in local rivers and flipped an anti-mining Shuar majority into a politically weak, minority. After centuries of mining resistance, gold became a temporary shortcut out of economic hardship in a context of increased state and market integration. As my collaborator Ringo calmly explained to me during fieldwork: “Currently, almost everything is about making money, but it can’t change us 100%, we are still Shuar.”

As to many others, Ringo’s turn to gold mining came after several years of internal deliberation in-and-among Shuar organizations, and a long struggle to find and scale up alternative livelihoods, notably cash crops and livestock production. Clearly, however, the increasing price for gold was and is, a major factor in the equation. Still, the Shuar turn to ASGM implied different engagements. Some families and individuals preferred manual panning with low stakes and risks; others worked as mine labourers; while others such as Ringo and his wife accumulated capital by charging external miners working on their lands until the point where they figured they might do it themselves. Today, Ringo and his wife own two excavators, purchased through retailers on credit, operated by their Shuar sons-in-law, engaged in a constant search for gold in both near and far-away rivers. Once in the mining game, the only way out of their debt is, ironically, to mine for gold since no other economic alternative can compete with its potential.

But why turn to gold in the first place? Why change from a relatively calm life of hunting, fishing, subsistence farming and small-scale cash crop production to the rollercoaster ride of gold mining? Indigenous Shuar communities are hardly immune to state and market integration, nor to modern material aspirations. Visions and desires move in a changing world, albeit in idiosyncratic turns. With the notable exceptions of groups such as the Taromenani and Taegeri living in voluntary isolation in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon, there is hardly any escape to state/market integration. On the contrary, echoing Daniel Tubb’s research with Afro-descendent gold miners in Colombia, Shuar communities in southern Ecuador are “already articulated with their own resource projects into global networks of trade”. Cash has been part and parcel of Shuar social life since at least the 1960s and trading has a much longer history. Indeed, Shuar mining resistance prevailed, especially against large-scale mining development, but increased access (e.g. roads, electricity, public services) spurred increased material needs. Shuar children needed school uniforms while desiring new things. Cars and chainsaws increasingly found their way into local dreams and practices alongside TV and technology. Poverty emerged as a local phenomenon. And people knew there was gold in the rivers since they occasionally panned it to supplement household economies. Hence, in 2017, the question was not if mining was going to happen, but rather who would do it.

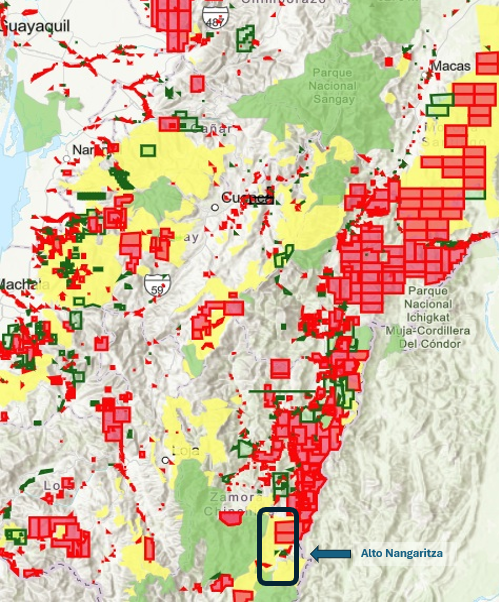

In light of the aggressive expansion of the mining frontier, notably state granting of LSM mining concessions and booming ASGM activity by local mestizo miners, we may perhaps understand why the Shuar communities turned to gold. Shuar communities have inalienable collective land claims that cannot be bought by externals, but the subsoil invariably belongs to the Ecuadorian state. This means that concessionaires can (legally) find their way into Shuar territories and exploit minerals for low compensation rates. Across intense deliberations, this plausible concern gained ground while the price of naranjilla, a key cash crop in previous years, dropped like a stone. Amid these circumstances, the vote for mining won in a large Shuar assembly and the search for gold commenced.

Clearly, this turn of events comes with deep ambiguities. Washington Tiwi, a long-term anti-mining proponent and current president of the largest Shuar federation in Zamora Chinchipe, remains highly critical of the socio-environmental destruction ASGM causes. And yet, he also recognises the capacity of local Shuar families to learn and appropriate the art of gold mining to their favour. Economic outcomes vary substantially – some families have earned good money while others are more indebted than before. Still, as Tiwi explains, if his Shuar constituencies had continued to resist mining categorically, external miners would have forced their way and captured most, if not all, revenue streams and only left the hazards.

Amid multiple concerns about deforestation, mercury contamination and path dependency, most ASGM ethnographers end up accentuating emic perspectives a la this brief story about the Shuar turn to gold. As long-term ASGM scholars point out, this is a crucial antidote to government criminalisation and widespread villainisation of ASGM miners since: “(…) without an understanding of mining ‘from within’, actions stimulating sustainability transformations – whatever they are – will be neither successful nor appropriate”. Nevertheless, and particularly in the face of the aggregate impacts of ASGM within the larger concern of deforestation in and beyond the Amazon, the larger concern of deforestation in and beyond the Amazon, this is somewhat an unsatisfactory end point.

Recent estimates based on satellite imageries of land covers, conclude that ASGM activity exclusively within indigenous territories in the Brazilian Amazon, has expanded by 625% across the last decade. Despite the attempts of Lula’s government to correct former president Bolsonaro’s alarming deregulation and Amazonian havoc, increasing gold prices continues to push this development across a point of no return. In Peru, accounting for almost half of South American gold production, military interventions against ASGM merely push mining into more remote areas. Colombia, upliftingly reducing deforestation in 2023, is similarly back on the destructive path with ASGM and coca cultivation, as the main drivers. Lastly, in Ecuador, the current neoliberal Noboa administration bound up with IMF conditionalities, is cutting public costs to the bone while doing its best to attract LSM companies into increasingly favourable, pro-mining indigenous territories in the wake of ASGM developments. The concerning ASGM situation resonates remarkably with the larger crises of climate change, biodiversity loss and increasing economic disparities, but lots of people indeed vote for politicians that neglect the problem and make (false) promises of economic bonanza premised on extractive exploitations.

Everyone carries strong imaginaries about gold. In the US fascinatingly connected to gold rushes in California and Klondike in late 19th century. Some are obviously more informed than others, but few people know that all the gold mined throughout human history amounts to a cube of 22 x 22 x 22 meters (approx. 212 000 metric tonnes) and that 2/3 of this has been mined after WW2. Also, in contrast to critical minerals supporting game-changing transformations – think about copper that essentially wired the world to (fossil) energy – gold’s “instrumental” use in electronics etc. is minimally at 15%. Almost half of all mined gold is transformed into jewellery while another 20-30% is bars and coins essentially playing speculative games with human minds. It is precisely here, at the consumer’s end and not in the Amazonian rainforest, that actions are required to break the spell of gold. “Give me an alternative and I will be the first to stop mining”, said Ringo last time I met him. Evacuating the Amazon from current threats will be a costly affair, increasingly so to compete with peaking gold prices. Yet, what is at stake is the well-being of the world’s largest terrestrial lungs. If they go down, all other climate measures are in vain.