The hair salon was located on Mbane Street where the buildings sagged and leaned at awkward angles like they’d run a marathon and were now catching their breath. The signboards were always crooked, the obsolete electric lines drooped even in cold weather, and the tarmac roads had large goose eggs that the electric bodaboda zigzagged to avoid.

We all knew what it meant, yet no one liked to talk about it, even after the heavy rains at the start of the month caused the Huduma Building to sink half a metre into the ground. Instead, we talked about how, with the rain, the dust was gone and we didn’t have to wear masks, how the rainwater tasted better than the recycled one we were used to during the dry season, and the locusts that came with it made a cheap tasty stew for ugali.

I brought the bodaboda to a stop at a single storey structure with peeling green paint and a faded name on its blackened windows “Sheme’s Palace.” On the rusted metallic door was a worn out, dog-eared poster informing the customer the store was split into a utility store at the back and a hair salon at the front that only opened during the rainy season when there was enough water.

Sheme had long ago given up maintaining the building’s aesthetic and decided to leave it to the will of the currents. After all, everyone still left in Magana Town knew her, knew her shop, and that if you wanted the best head massages or cockroach pesticide you went to her.

I ducked inside the store now tinged with a musty smell expecting to be met with laughter and voices talking over each other as they traded the latest gossip in Magana, but it was quiet and empty. Odd for a Saturday, people were home—well, people were always home since the passing of the Work from Home Bill to help reduce CO2 emissions—and it was the rainy season, a golden opportunity for them to get a full salon experience.

Sheme emerged from the grill partitioned side that was the utility store, selling everything from nails and screwdrivers to sanitary products. She paused, her forehead creasing. “Haiya! You’ve come?”

“Yes, I’m back.” I hesitated, passing my tongue over my lip as I weighed the next words. “And I’m sorry… for storming out the other day. If you hire me again, I’ll follow all your instructions.” I’d had a week in seclusion to conclude it hadn’t been one of my best moments, frankly it had been my worst.

The disagreement had been over me doing three rinses instead of two during washes. I thought three was more refreshing than two seeing as how during the dry season we barely had enough water to drink let alone wash our hair. This had been my deciding factor for going bald.

“Mmm.”

I waited as she processed my apology, eyes bouncing from her wrinkled face to a poster showing how to purify rainwater.

I needed this job. The shipping company I’d worked for had closed its Magana branch, leaving me jobless. The only other place hiring was the Fire Station and I wasn’t qualified enough.

Sheme straightened her back and met my eyes. “Doti, have you not seen the group messages?”

“Uh, no.” I fiddled with the zipper of my thermal jacket, too embarrassed to admit I no longer had electricity. My solar batteries had gone bad and without money, I couldn’t replace them. My phone had died shortly after leaving me no other choice but to plaster a new web of cracks in my sitting room, clean my water filters, and weed the garden.

Sheme reached into the black and yellow leso tied around her waist and pulled out her phone, she turned it on and passed it to me.

On the screen was a poster.

My heart stopped at the bold words in bright blue. “We’re being evacuated?”

“Mmm, the geologist predicts in less than two weeks the village will be completely covered by a landslide.”

My ears rang with the news.

No, not again.

I slid down on the waiting bench backed against a moulding wall, clutching my pounding chest as my head filled with images of a crumpled building I’d once called home.

“But where would we go?”

Further North was desert, inhabitable; the Coastline was sinking and currently dealing with a squall; the Capital was smog filled and housing was expensive; in the West, River Tamu had broken its banks displacing hundreds of thousands; and the South was more desert.

Sheme sat next to me and said in a gentle tone, “They’re setting up a camp.”

A pit settled at the bottom of my stomach. Camps were where hopes went to die—crowded with poor sanitation, a breeding ground for diseases, high cases of violence, and no way out.

“We can’t leave.”

“We don’t have an option.”

Despair squeezed my lungs. I couldn’t believe it, twenty three years on this planet and I was losing my home for the second time. The first time an earthquake had collapsed our apartment building with my parents in it while I’d been sent to the shop. It had taken them a month to sort out their limbs from the rest.

Sheme patted my thigh. “You should go home, maybe start packing. I want to close down.”

On my way back, I noticed what I hadn’t before in my nervous state; the shops were closed or closing. The seed and cereal shop—closed; the clothing store that only last week had been stocked with the newest thermal wear for the cold weather—closing; the electronic shop that did repairs and collected lead batteries—closing.

This was really happening.

My house, a two bedroom leaning structure left to me by grandmother, stood alone at the edge of the town beyond which was the encroaching desert. My neighbours across had long moved, blessed with the right connections to secure them a home in the newly built Fangano City that had been advertised as ‘a city that changes with the environment.’ My neighbours to the right died the same time grandmother had, during a cholera outbreak a year ago.

On the doorstep was a government issued green duffel bag tightly folded, attached to it was a laminated set of instructions on how the evacuation process would go. It said I had three days to pack before the evacuation bus came and took us to a resettlement camp ten kilometres east of here for those with no other options, failure to comply would result in forceful evacuation and relevant fining as prescribed by the Disaster Management Bill.

I thumbed the bag then eyed Grandma’s garden that had been her pride and joy, the kale had sprouted, the tomatoes were turning colour, and the mushrooms had fattened. To imagine all of it covered by soil made my eyes well with tears. I spent two days lamenting my fate and cursing the universe before I got myself together and did as instructed.

I’d wait for the bus because I had nowhere else to go and it was best I preserve the little power my bodaboda had.

The bag fit all my clothes easily. I only had two sets, light wear for the hot season and heavy for the cold, five pairs each. Everything from the garden I put in a kiondo that I held on to tightly as the bus rattled along the lumpy road heading east to my new home.

***

The less than two weeks estimation ended up being a stretch.

I was having a hard time adjusting to sleeping on a thin mattress over hard ground. It was worse when it rained, which it had every night since we got here. Raindrops drummed hard on the tent, and I kept worrying rain would spill inside or the tent would be blown away, but so far none of that had happened.

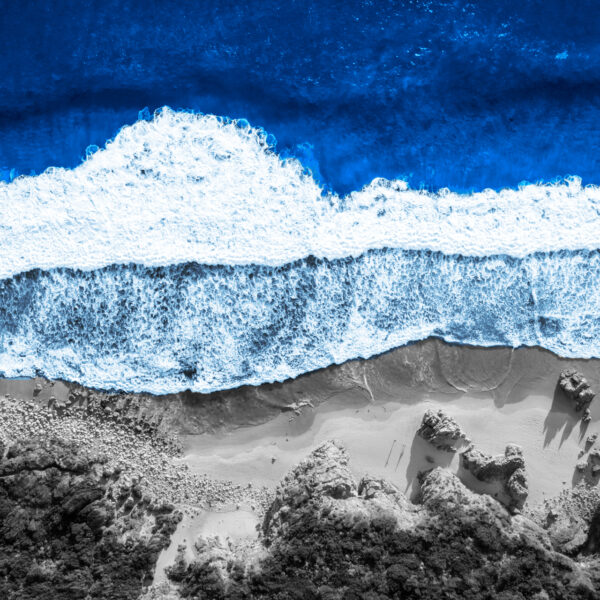

On the third night, after the rain had died down to showers, I got up to use the outhouse. As I weaved through the tents, I heard a distant rumbling like a wave crashing onto land. It grew louder, waking half the camp.

Our attention turned west, where Magana sat on a steep slope. Its solar powered street lights were still on; an indicator the town was still there. We gathered at the edge of the camp and watched with bated breath as one by one the streetlights began to flicker and go dark.